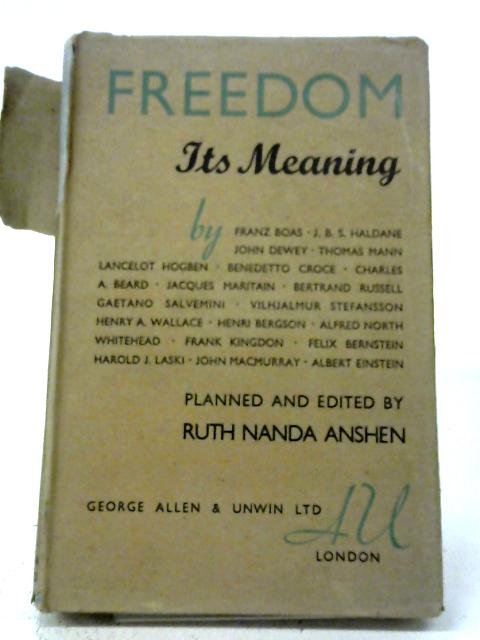

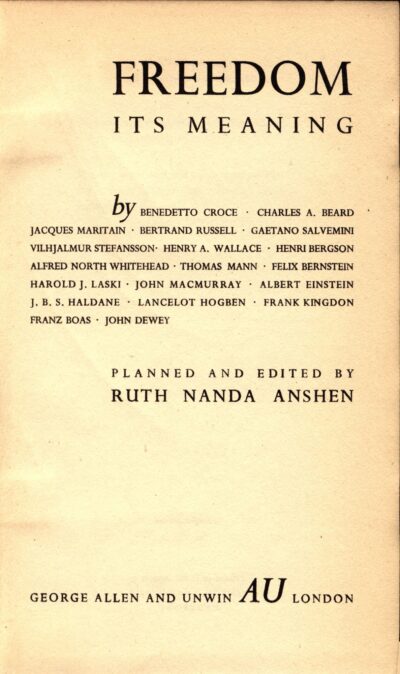

Ruth Nanda Anshen (ed), Freedom: Its Meaning (1942)

Ruth Nanda Anshen was an American philosopher and author, who dedicated her life to interdisciplinary studies and ensuring that great thinkers in various fields learned how to communicate with one another.

Born in Massachusetts in 1900 as the daughter of Russian immigrants, Ruth’s mother was a celebrated poet and her father translated religious texts. Such a background exposed Anshen to both ideas and creativity, and inspired her to pursue a PhD at Boston University. Attending the Harvard Tercentenary in 1936, she was distressed that the brilliant ideas presented by scholars from all over the world, from physicist Albert Einstein to geneticist J.B.S. Haldane, seemed to stand in sterile isolation, obfuscating rather than truly enabling knowledge. She resolved to pursue a ‘unitary principle under which there could be subsumed and evaluated the nature of man and the nature of life, the relationship of knowledge to life’. She won Einstein’s backing, and began producing the ‘Science of Culture’ series of books, that would run for decades, but the first of which was entitled Freedom: Its Meaning and features over 40 essays with authors like Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Henri Bergson, Thomas Mann, Hu Shih, and many other leading minds of the twentieth century.

In the introduction, Anshen explains the book’s premise as follows:

‘Man alone, during his brief existence on this earth, is free to examine, to know, to criticize and to create. In this freedom lies his superiority over the resistless forces that pervade his outward life. But Man is only Man — and only free — when he is considered as a being complete, a totality concerning whom any form of segregation is artificial, mischievous, and destructive, for to subdivide Man is to execute him. Nevertheless, the persistent interrelationship of the processes of the human mind has been, for the most part, so ignored as to create devouring distortions in the understanding of Man to the extent that one begins to believe that if there is any faith left in our seemingly moribund age it clings in sad perversion, in isolated responsibility, and with curious tenacity to that ancient tenet: “Blessed is he who shall not reveal what has been revealed unto him.”’

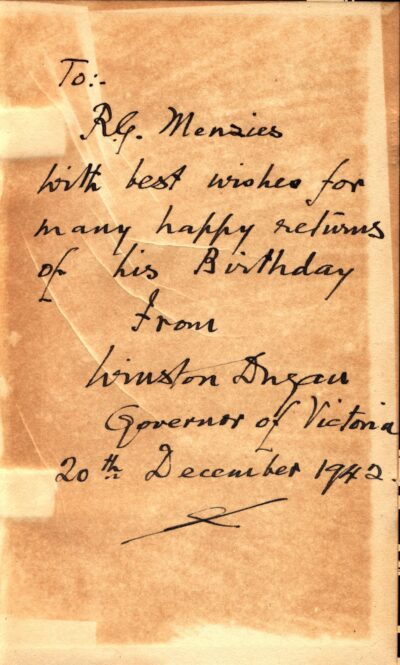

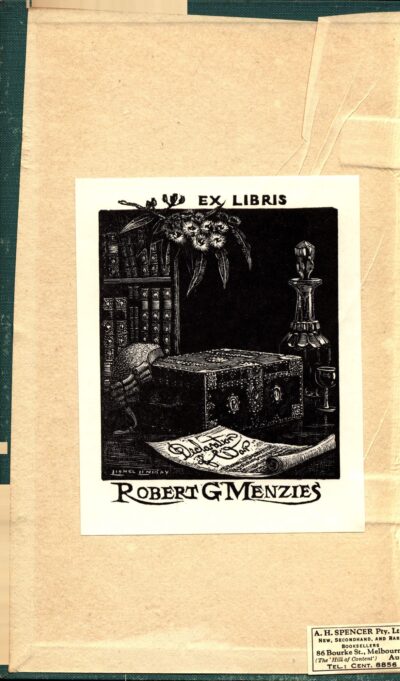

This idea would undoubtedly have appealed to Menzies, who likewise opposed the atomisation of knowledge and argued for the necessity of a lifelong liberal education (of which the Menzies Collection itself is a testament). His copy of the book was a birthday gift from Winston Dugan, Governor of Victoria, given on 20 December 1942. The gift marked the end of an extraordinary year, during which Australia had faced its greatest ever peril, and during which Menzies had delivered 51 weekly radio broadcasts reacting to events like the bombing of Darwin, but also unpacking political philosophy beginning with Menzies’s famous Forgotten People Broadcast delivered on 22 May.

Menzies had spent many episodes examining Roosevelt’s four freedoms, as well as other complex topics like ‘The Nature of Democracy’, ‘The Moral Element in Total War’ and ‘The Importance of Cheerfulness’. Although there is no direct attestation of this in the book’s inscription, it seems likely that the Governor himself may have been listening to the broadcasts (the earliest of which made such a splash that they were reported in the New York Times and both Houses of British Parliament), and he may have been intent on providing Menzies with more food for thought. Notably the book and the broadcasts are examples of the same global phenomenon, namely the manner in which the war prompted a mass wave of reflections on the nature of humanity, political institutions, and ultimately how to build a better world.

Essays that seem likely to have struck a chord with Menzies include:

- Felix Bernstein, Professor of Biometrics at New York University, on ‘The balance of Progress and Freedom in History’ in which he argues that ‘any progress really made by mankind cannot endure unless it becomes thoroughly anchored in the existing culture’.

- Edward Samuel Corwin, Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton University, on ‘Liberty and Juridical Restraint’ which traces the emergence of the American tradition of constitutional liberty through Cicero, John of Salisbury, Magna Carta, John Fortescue, Edward Coke and John Locke.

- Frank Kingdon, President of Newark University, on ‘Freedom for Education’, which argues that education is ‘an instrument for survival’ through which man must constantly adjust himself to the changes wrought by human progress.

- John M. Clark, Professor of Economics at Columbia University, on ‘Forms of Economic Liberty and What Makes Them Important’ which emphasises the centrality of having a choice of occupation with multiple potential employers if one is to have real personal liberty – a line of arguing against socialism which was to have great cut-through in Australia in the 1940s.

- Gaetano Salvemini, Lauro de Bosh Lecturer in the History of Italian Civilization at Harvard University, on ‘Democracy Reconsidered’ which suggests that the true basis of democracy is an acceptance of human fallibility and therefore the need to constantly hold governments to account.

- Jacques Maritain, Professor of Philosophy at the Catholic Institute of Paris and the Institute of Medieval Studies of Toronto, on ‘The Conquest of Freedom’ which uses Thomist philosophy to suggest that true freedom requires the acceptance of one’s dependence on God, recalling Menzies’s phrase that ‘Human nature is at its greatest when it combines dependence upon God with independence of man’.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.