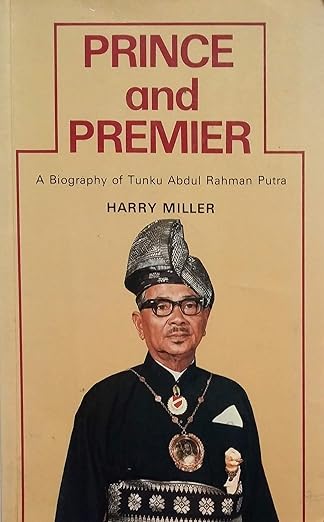

Harry Miller, Prince and Premier: A Biography of Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, First Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya (1959)

While Robert Menzies’s commitment of Australian troops to Vietnam towards the end of his record-setting rein as prime minister has done much to define how he since been remembered, his first military commitment after being elected in 1949 has been largely forgotten. In many ways, Australia’s involvement in the Malayan emergency, first announced on 31 May 1950, was the anti-Vietnam. In the sense that not only was the decision to become involved made at the opposite end of Menzies’s prime ministership, but it meant assisting the British rather than the Americans and of course the end result was an enduring success rather than a humiliating failure.

There were several reasons for this. In Malaya, support for the communist rebels was largely confined to a Chinese ethnic minority – whereas in South Vietnam it was a Catholic religious minority that was associated with the ruling Diem regime. And even so, the British were more successful in winning the ‘hearts and minds’ of that minority through humanitarian aid and building programs than their US counterparts. The Australian effort also benefitted from the cultural connections of the Commonwealth, and the fact that the British were far more open to letting Australians be actively involved in key strategic decision making than the Americans.

The long-term benefit of the commitment was twofold. Firstly, it helped to stop the spread of communism and establish security in our region. Secondly, it fostered a new ally and trading partner. The intimate relationship that the Menzies Government was able to develop with first Malaya and then Malaysia is one of the forgotten triumphs of our initial engagement with Asia, or as Menzies dubbed it our ‘near north’.

When Malaya gained its independence in 1957, the newly-elected government asked the Australian troops to stay and continue to help mop up the last pockets of communist resistance. Even after the emergency was declared over in 1960, we were asked to stay on longer, providing a garrison that would ultimately end up fighting on Malaysia’s side once more during its confrontation with Indonesia. In 1958 we signed a trade agreement with Malaya, which became a major market for Australian goods, particularly flour, in exchange for the importation of necessities like rubber. Malaya also provided one of the largest contingents of international students who came to Australia to study under the Colombo Plan, and in years to come Malaysian administrations would often feature many leading figures who had a direct connection to Australia as a consequence.

All of this beneficial interaction was personified in the close relationship that developed between Menzies and Malaya/Malaysia’s first prime minister and ‘founding father’, Tunku Abdul Rahman. Who visited Australia in one of his first official diplomatic trips in November 1959 – which is when he gifted Menzies his copy of Prince and Premier. This was a courtesy that Menzies immediately repaid by travelling with Dame Pattie to Malaya in December that year. An occasion Menzies used to meet with the Australian troops dealing with the final stages of the emergency, and also inspect how Australia’s Colombo Plan aid was resulting in tangible improvements, such as a 210-bed hospital specialising in the treatment of tuberculosis patients. Many of the doctors and nurses practicing in it were either Australians themselves, or had been trained in Australia. Other assistance included help in developing a central banking system, establishing a medical faculty, making provision for Malayan engineering students graduating in Australia to gain some experience on the Snowy Mountains project before returning to Malaya, and in codifying the existing three distinct sets of law.

Menzies and Tunku would meet several times over the years, as well as frequently exchanging private messages. Notably – given that it is often cited as one of the main barriers in Australian-Asian relations at the time – Tunku refrained from criticising the White Australia Policy over this time, telling reporters that it was ‘entirely a domestic issue’. When Menzies retired in 1966, Tunku was prescient in paying tribute:

‘a great loss to Australia which he has served so well and so honourably. Historians I dare say, will speak of this as the Menzies era. He will be greatly missed at Commonwealth conferences where he has always been a great friend of Malaysia. Right through all this troubled period we have had with Indonesia Sir Robert has been one of our strongest supporters, has always been one for direct support, and one who has tried to persuade other Commonwealth countries to show more than sympathy for a country made the victim of Indonesian aggression’.

In his memoir, Afternoon Light, Menzies returned the favour by describing Tunku as ‘my friend’, and praising his moderate counsel in what were often heated Commonwealth discussions surrounding South Africa in the 1960s. Allan Dawes’s unpublished biography of Menzies contrasts his subject’s close relationship with Tunku with his strained dealings with Indian leader Nehru, suggesting that it was matters of policy and principle, rather than race, that determined the attitude in each case.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.