Among Sir Robert Menzies’s greatest legacies is the fact that he made university education a ubiquitous part of Australian national life. His government introduced a comprehensive system of merit-based Commonwealth Scholarships that helped ensure that those with the intelligence and drive to pursue higher education were granted the opportunity to do so, irrespective of their parent’s financial situation. This was an avenue of social mobility and self-actualisation that was very dear Menzies’s heart, given that he himself had only been able to attend the University of Melbourne thanks to winning one of just 25 ‘exhibition scholarships’ that were available at the time.

Like many of Menzies’s accomplishments, the growing pervasiveness of university education is a change that is so fundamental to modern Australia that we now largely take it for granted. Forgetting that there was once a time when not only was the chance to earn a degree a rare privilege, but also when many Australians actively looked down on university graduates for being snobby and well-off. For this reason, up until the Second World War the Australian Public Service openly discriminated against graduates in its recruitment processes, because it did not want to be seen to be providing job opportunities for those who were already wealthy.

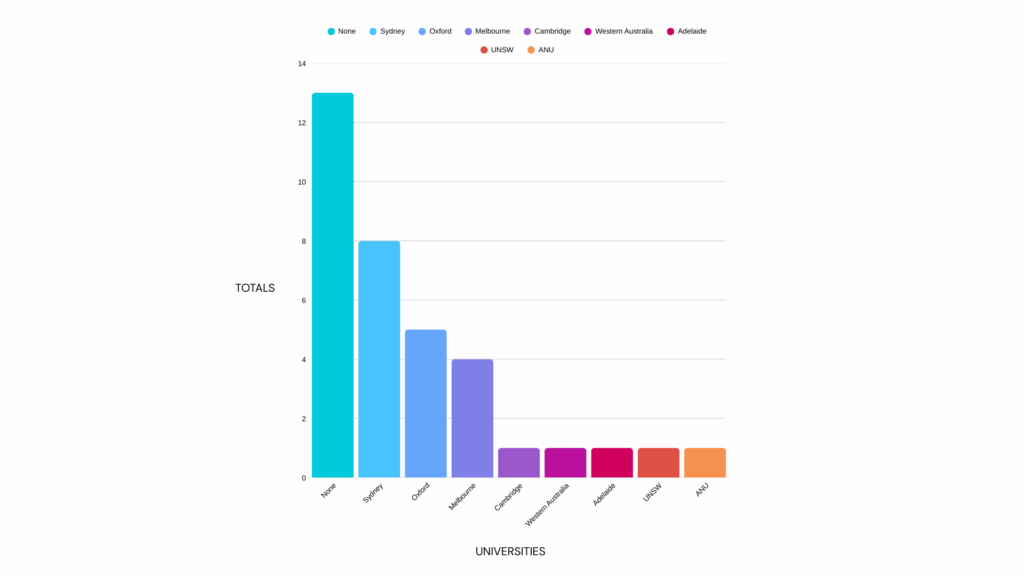

Such was Australia’s tall-poppy syndrome surrounding higher education, that the electorate did not even expect our political leaders to have attended a university. In fact, up until Menzies’s retirement in 1966 it remained exceptional for them to have done so, with just 5 of our first 16 Prime Ministers having earned a Bachelor’s Degree. Since Menzies’s retirement, the situation has been completely reversed, and there have thus far been only two additional degree-less PMs – Country Party caretaker John McEwen and most recently Labor’s Paul Keating.

Keating not only represents the last of a dying breed, but he also epitomises an essential culture shift within the ALP, which up until Gough Whitlam was elected in 1972 had not had any of its Prime Ministers attend university (although Billy Hughes had obtained some legal qualifications through part time study once already in Parliament). This speaks not only to the idea that Labor has been gradually moving away from its working-class roots, increasingly drawing membership from white collar public service unions over blue collar manufacturing ones. But also that Menzies was so successful in growing real wages, rates of homeownership and the consequent size of Australia’s middle class, that the only way for Labor to win back office was to self-consciously start trying to appeal to that class, as it did through the Whitlamite program of social progressivism and free university. Although unlike Menzies’s merit based scholarships, the latter system proved to be so financially unsustainable that it had to be subsequently shelved by the Hawke Labor government despite its apparent popularity.

Previously, Australia’s political parties had been largely class based, which is attested in the educational attainments of our PMs. Despite there being 13 PMs without a university connection, Free Trade Liberal George Reid is the only one of those 13 to have never been a member of the Labor or Country parties. To this day, there have still been more Labor PMs without a degree than with one (8 v 5).

Our female PMs have all been university educated, by virtue of there only being one in Julia Gillard, and one might suggest a correlation between Labor’s quota-driven rise in female representation and its drift away from the industrial working class. In the Menzies era, it was the Liberals who were supposed to be better at cultivating the ‘women’s vote’. This was in part because Menzies talked a lot about the family home and budgeting, which obviously included women, whereas Labor focused on industrial relations at a time when women were excluded from many workplaces. Although it should be noted that Menzies was a strong advocate for more women getting degrees and consequently entering the workplace, declaring in one of his Forgotten People broadcasts delivered as early as 1942 that ‘higher education for women must come to be regarded as normal and not as the eccentricity’.

But what about the universities themselves, which gets to claim top honours as the greatest producer of our political leaders? That prize goes to the University of Sydney, which can boast of 8 including our first PM in Edmund Barton, although its lead is largely made up of recent history, with 6 PMs since 1971. When Menzies was succeeded by fellow University of Melbourne alumni Harold Holt in 1966, that uni held the lead over Sydney 3-2, but it has since only added Gillard to its list and it has to share her with the University of Adelaide. Perhaps most surprising is that Melbourne has now been further overtaken, with Oxford sitting in second with 5, in part due to the prevalence of Rhodes Scholars like Bob Hawke and Tony Abbott. Cambridge, Western Australia, ANU, Adelaide and UNSW all share fourth place with 1 each, with the sandstone universities holding a near monopoly, and the ‘Group of Eight’ a real monopoly, of PMs who have graduated from Australian institutions.

As of 2024 77% of the members of Federal Parliament held university degrees, suggesting that another Keating is becoming an increasingly unlikely possibility. But while this is generally a positive change, there is an argument to be made that since only 32% of the broader population hold degrees, our parliament is now less reflective of the educational diversity of the Australian public than it once was.

Indeed, while no one respected the importance of university (and a liberal education specifically) more than Robert Menzies, it is clear that he equally did not think that university was for everyone. He thought that if universities grew increasingly homogenised to deal with an influx of too many students they might lose that mystical pursuit of ‘truth’ that made them valuable in the first place, hence the introduction of Colleges of Advanced Education to take the pressure off of university enrolments in the latter years of his government. With AI not only threatening to take the jobs of a range of university graduates, but also weakening the ability of universities to rigorously evaluate their students, it could mean that the utility of mass higher education has peaked, and it might once again become a more selective pursuit. But even were this to prove the case, it is hard to imagine Australia ever returning to a place where graduates were actively looked down upon. For Menzies has won the university an enduring place in our national culture.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.