Article by Zachary Gorman first published in Teaching History: Journal of the History Teachers’ Association of New South Wales Volume 59 No. 2 2025:

The 1950s represents a unique period in the teaching of civics and citizenship in Australia. The concept of Australian citizenship, as distinct from British subjecthood, had only come into effect on 26 January 1949, and a wave of post war migration from outside the British Isles was transforming what it meant to be an Australian under the imperative of ‘populate or perish’.

In this context, education was not limited to schoolchildren and vast resources were invested in elaborate annual Australian Citizenship Conventions held in Canberra over each Australia Day period. The aim of these conventions was to inculcate recent migrants in Australian values and the duties and expectations of citizenship, while simultaneously reassuring the public that the newly broadened definition of ‘White Australia’ did not pose a threat to those values.

At the primary school level, advances in pedagogy were leading to the implementation of new ‘social studies’ curricula, combining history, geography and civics into one subject, across the various Australian states. These curricula saw a move away from a focus on Empire (and the exercise of globe-spanning imagination which its conceptualisation required) towards an emphasis on tangible lived experience.[i] The curricula focused on ‘widening horizons’ outward from the family, to the local community, and ultimately the nation, in a manner that was designed to be a relatable demonstration of the interdependence of society.[ii] This included the ‘dependence of man upon man, city life on rural life, and nation upon nation’.[iii]

For this reason, the new curriculum adopted for New South Wales in 1952 taught students about political machinery by beginning with local councils and only gradually graduating upward towards what went on in Canberra.[iv] Also embedded in the teaching of civics was a Whig narrative of Australian progress, ensuring that ‘the child increases his awareness and understanding… of the general trend of changes and reforms that will make his whole material and social environment a better place in which to live.’[v] So, lessons were not limited to how governments functioned, but instead, they enlivened the subject matter by exploring what they had actually achieved over the years, including comparison with the poorer living standards endured by those in the past. This formed part of the ‘tangible’ teaching approach, while also delivering the message that Australia was on an upward path of material progress.[vi]

There was some criticism that the curriculum downplayed the teaching of civics and history by eliminating their stand-alone status, and that it emphasised student interests and projects over comprehensive content. However, it did encourage the discussion of the achievements of leading Australian democratic figures, including William Wentworth, John Dunmore Lang, and more recent prime ministers Stanley Bruce and Ben Chifley.[vii] It also examined international exemplars of ‘citizenship as service’, like Hellen Keller and Florence Nightingale, reflecting an understanding of civics as a form of moral education.[viii]

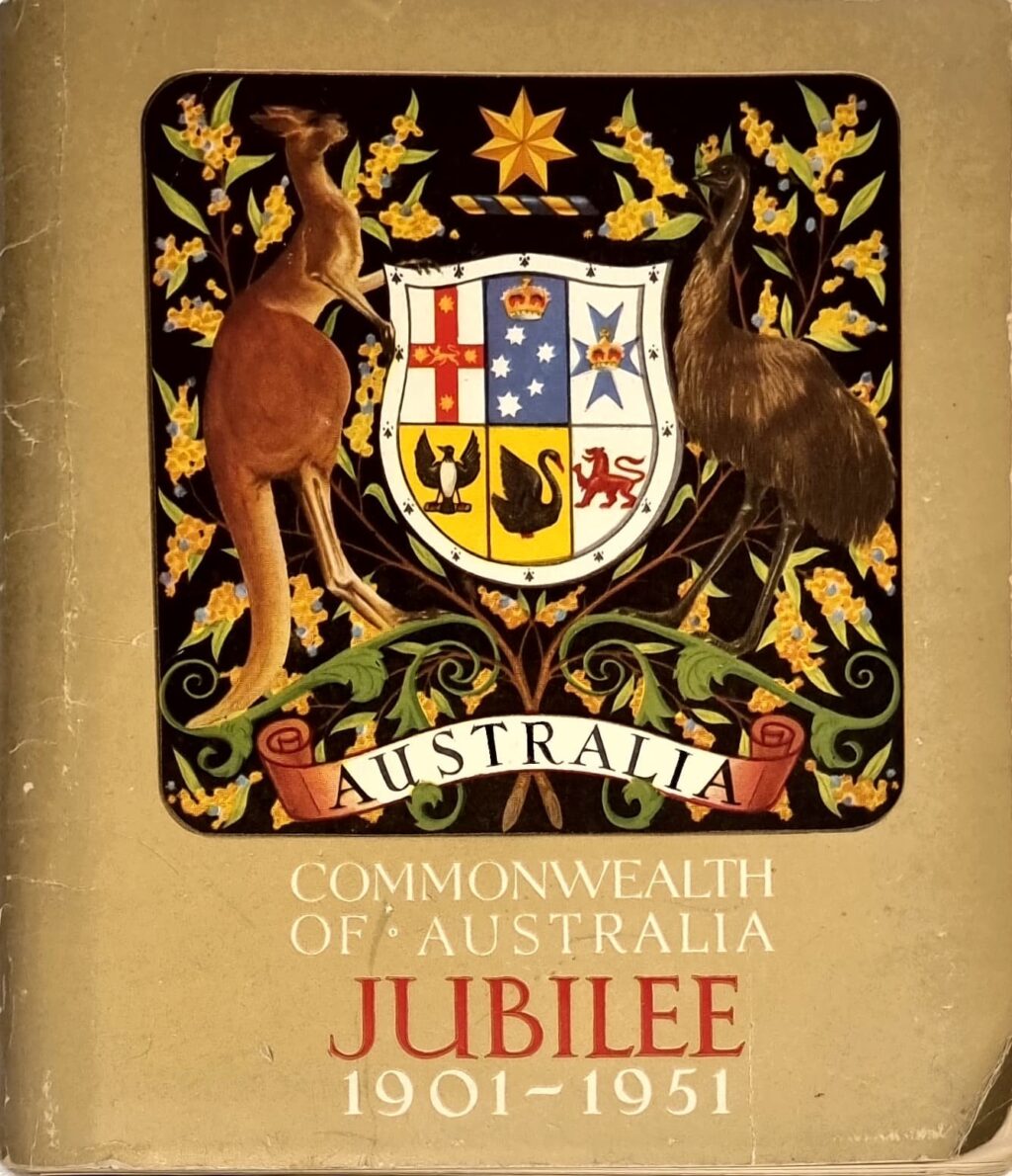

While there was no national curriculum, and education was still viewed as a matter constitutionally entrusted to the states, the 1951 Jubilee of the Commonwealth of Australia saw the federal government take on a proactive role in propagating ideals of citizenship and civics to students of all ages. Every school in Australia, both public and independent, was provided with an Australian flag to fly on its flagpole and encouraged to organise elaborate pageants and film projections marking the Jubilee.[ix] Each primary school child received a commemorative medal, and each secondary school student, a commemorative booklet, complete with a space to inscribe their name and school to keep as a proud memento of the occasion.

Spanning over forty pages, numerous copies of the booklet survive and they offer a fascinating insight into what the Menzies Government expected young adults to know about Australia’s history, constitution, and political and social evolution from 1788 until 1951.[x] The content has some of the deficiencies you would expect of the period, most notably in the limited space it gives to discussing First Nations Australians. But it equally reflects the ‘modern’ concerns of the decade, and its positive narrative was intended to give students an empowering sense of their own place in an ongoing national story.

That story revolves around a triumphalist narrative of taming the land, winning democratic freedoms and building prosperity. It encouraged an appreciation for just how far Australia had come from the days of convictism, military rule and autocratic governors, and the effort that went into each step along the journey. The initiative shown by heroic reformers like Governor Lachlan Macquarie and Willaim Charles Wentworth is frequently lauded, but equally, there is an explanation of evolving democratic machinery; from the first Advisory Council established to check Governor Thomas Brisbane, to the implementation of a partially elected Legislative Council in 1842, to the granting of responsible government in the 1850s, and reforms like the secret ballot (which was invariably boasted of as an Australian invention). The story of each of the colonies is interwoven into one Australia-spanning narrative, but the booklet is not afraid to highlight their distinctiveness, such as the idealistic and experimental intent which shaped the convict-free colony of South Australia.

The story of federation is framed in terms reflecting the era’s evolving conception of Australian identity. The authors are keen to emphasise that Australia had never been comprised exclusively of people from the British Isles: there had been Germans, Americans, and even the preaching efforts of Spanish Catholics. They likewise explain that federation was not accomplished by ‘native born’ men alone; immigrants like Henry Parkes, depicted as an embodiment of Australian social mobility for arriving with just four shillings in his pocket, made essential contributions. Notably, Britain and Empire are less prominent than they might have been before World War I, as the booklet explains that ‘Federation was not an imperial gift. The Constitution was worked out by Australia’s own leaders and established by democratic ballot taken among the Australian people’.

The Constitution itself forms the centrepiece of the booklet, which describes the Jubilee as a celebration of its establishment. Here the triumphalism is tempered by a more realist depiction of democracy as the art of compromise:

As you can imagine, it was not an easy thing to fit together several independent governing bodies… The result was not a perfect document, but a practical compromise. The men who made the Constitution depended upon their experience of local conditions rather than upon book-learning or abstract theories.[xi]

The booklet went on to explain the separation of powers, function of the two Houses of Parliament, how to form government, alter the constitution, the roles of the Cabinet, Governor General and High Court, and more. An appreciation of Australia’s evolving place in the world is reflected in the description of Canberra as a planned city, drawing comparison to not just Washington DC but also New Delhi. World War II had made it a ‘recognised world capital’, and it was now teeming with ambassadors and diplomatic legations, all keen to hear Australia’s united voice.

Prime Minister Robert Menzies provides a personal introduction at the start of the booklet, where he admits that the first fifty years of the Commonwealth’s existence had been far from smooth sailing, involving two world wars and a great depression. But, he noted, ‘the courage and determination of the fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters of those who will read these pages, helped us win through’.[xii] This sense of shared endurance, and a bipartisan commitment to the ‘Australian Settlement’, meant that the authors could be more boastful about the policy achievements of Australian democracy than a successor might be today. They included tariff protectionism, the implementation of a ‘living wage’, the Old Age Pensions Act, the trans-continental railway, Snowy Hydro Scheme and the Australian National University. These embodied the prevailing materialist conception of progress, in which the Commonwealth was expected to ‘fulfill its name by treating all citizens fairly and giving them a high standard of living’.[xiii]

Improving and egalitarian living standards were not just a core component of the Commonwealth’s mission and a defining characteristic of Australian history for which a variety of agricultural and industrial pioneers were given credit. They were also the central message that Australia wanted to preach and exemplify to the wider world:

In the past we have been fortunate in our great men… We must continue to encourage such men and do all that we can to use our increased importance amongst the nations in world councils to raise the living standards of countries less fortunate than ourselves.[xiv]

This developmental internationalism took policy form in the Colombo Plan, which involved a further erosion of White Australia to allow for an influx of Asian students. In turn, they would help prompt a further evolution of Australian identity towards something we would recognise today.[xv]

All told, the key lesson learned from the teaching of citizenship and civics in the 1950s is the power of the narrative to carry information and inspire students. While we would now expect more nuance and a greater recognition of the darker chapters of our past, it is interesting that such updates were already taking place when it came to issues of migration and Empire. It is equally curious that parallel or even contradictory narratives were able to be accommodated when it came to the distinctive states, suggesting that there is scope to adapt aspects of this narrative teaching to the concerns about civics education in the present.

[i] Vicki Macknight, ‘The Politics of Pedagogy: Civics Education at Victorian Primary Schools, 1930s and 1950s’, History of Education Review 36, no. 2 (2007): 46-60.[ii] Rodney Louis Reed, ‘A Comparative Study of Primary School Social Studies in Three Australian States’, Masters’ Thesis, University of Melbourne, 1976.

[iii] Donald McLean, ‘The Social Studies Syllabus’, Education: The Journal of the NSW Public School Teachers Federation 33, no. 11 (July 1952): 80.

[iv] The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 30 March 1953, 2.

[v] Education Department of N.S.W., Curriculum for Primary Schools – Social Studies, (Sydney: Government Printer, 1952), 178.

[vi] Macknight.

[vii] SMH

[viii] Kerry Kennedy, ‘Civics Education in Post World War II Australia: The School Curriculum as Conservative Policy Text’, Asia Pacific Journal of Education 21, no. 1 (2001): 19-29.

[ix] Daily Telegraph, 16 December 1950, 14.

[x] Commonwealth of Australia, Commonwealth of Australia Jubilee 1901-1951 (Canberra: Government Printers, 1951).

[xi] Please add source and page ref

[xii] Page ref

[xiii] Page ref

[xiv] Page ref

[xv] Daniel Oakman, “Young Asians in our homes”: Colombo Plan Students and White Australia’, Journal of Australian Studies 26, no. 72 (2002): 89-98.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.