Every now and then, a government, seemingly enjoying almost supreme ascendancy, inadvertently lets slip a revealing comment that comes, in time, to define the very reason ordinary voters will eject them from power.

This month marks the 80th anniversary since John Dedman, the Labor Minister for Postwar Reconstruction, did Robert Menzies the profound favour of serving up an offhand riposte during Parliamentary debate. This moment effectively defined the difference between the Labor and Liberal Parties on housing, and what is meant when Australians use the word “home.”

On Tuesday, October 2, 1945, Dedman, a member of the Chifley post-war Labor government, was speaking in the debate on the second reading of the Commonwealth and States Housing Agreement Bill. He rejected a suggestion that people should be encouraged to own their own homes.

“The Government is not concerned with making people into little capitalists,” he declared, thereby providing the line that Menzies and the Liberal-Country Party coalition would still be referencing four years later, in the election campaign which brought Menzies to the Prime Ministership in December 1949.

The moment Dedman dropped this verbal bomb, Country Party MP Doug Anthony Sr. interjected, “Not concerned with making them home-owners: that is what you mean!” Dedman steadfastly ploughed on, arguing that “too much legislation passed recently has tended to give people a vested interest in capitalism,” a policy which would never have his support. The reaction was immediate enough that the following day Dedman made a grudging retraction, allowing, (one imagines, through gritted teeth) “I believe in the right to own your own home.”

The cat was out of the bag, however. Launching his party’s election campaign four years later in 1949, Menzies declared that he would amend the Commonwealth-States Housing Agreement “so as to permit and aid ‘little Capitalists’ to own their own homes.” The line had stuck.

It’s not hard to see why. Labor’s post-war reconstruction agenda, state-driven and mirroring the Labour Atlee government in Britain, focused heavily on social and rental housing, following closely the Beveridge Report’s preoccupation. Deeper than that, the policy sprang from an historic Labor suspicion of land ownership, traceable to Henry Georgite origins—where land wealth was condemned as “unearned increment,” and a single tax on unimproved land value would effect what Zachary Gorman described as “a pseudo nationalisation of land.” For the ALP, it was simply “housing,” another social provision to be made, rather than a preoccupation with “homes” as central to the life of individual families, the building blocks of wider communities, and the broader national life.

This was a great obstruction for Labor because it flew in the face of the intense “land hunger” that had defined Australia since its earliest days. The passionate desire to own a piece of earth was definitional for generations of new arrivals, who had come from countries where property ownership was a remote prospect. Britain’s Enclosure Acts had sent whole swathes of the rural population into newly emergent towns and cities, whilst Irish Catholics were systematically deprived of access to land ownership. No surprise, therefore, that the whole notion of home ownership early established itself in the emerging Australian ethos and mindset.

Colonial Liberalism’s decades-long campaign to “Unlock the Lands,” which began in the 1850s, with the famous (and notorious) Land Conventions in Victoria, and subsequent series of Land Selection Acts, was mirrored in NSW with John Robertson’s Land Selection Act (recently discussed in the Afternoon Light podcast episode featuring an interview with Robertson’s biographer, William Coleman,) and culminated in the Crown Lands Act of 1895, passed by Lands Minister Carruthers in George Reid’s NSW government. This Act finally secured the opportunity for would-be farmers to acquire homesteads and begin farming in large numbers. This move to democratise land ownership was a core aspect of the pre-Federation political DNA.

The Menzies family story exemplifies this ethos. Menzies was born in Jeparit, where his family store depended on the custom of new farmers establishing themselves on land created by dividing enormous pastoral runs. The Menzies Store was the town centre of a district of new farmers in newly established homesteads, who relied on Kate and James Menzies for everything from millinery, drapery and suits “made to measure” (in the words of one early advertisement,) to ironmongery, groceries, boots and shoes.

This was the home Menzies was born into, and it was from here that his own profound sense of home—and the family life it makes possible—as the existential bedrock of a life worth living, was formed.

The home was a cornerstone, not a social policy merely. Menzies saw early, and from close up, the degree to which “the home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health of society as a whole,” where a whole community is built – and builds itself, out of the common and cooperative aspiration to establish a stake in the country by building a home in which to live which constitutes a true place of one’s own.

For Menzies, homeownership means personal incentive, family formation & a stake in the community. This is why “the real life of this nation” is to be found in the homes of ordinary Australians who, “whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race.”

One can see why Menzies and the Liberal Party would fasten onto Dedman’s “little Capitalists” comment with such vigour.

The word “home” was the emotional and political centre of both his 1946 and 1949 election campaigns. In Menzies’s vision this campaign was closely linked to the notion that home was where Australians would base their families and prepare the nation’s next generation.

In power from 1949, the Menzies Government did more than any other in Australian history to make the dream of home ownership a reality. Commonwealth financial grants to states were increasingly geared towards home ownership. Housing interest rates were kept low by the Commonwealth Bank (then operating as the central bank), hovering below 5% for the 1950s decade. The post-war boom, with full male employment on consistently rising wages, saw the housing stock in metropolitan Australia double from 1947 to 1966.

Home ownership lifted from 53% in 1947 to the historically high level of 73% when Menzies left office in 1966.

Australia had become a nation of “little Capitalists,” with The Great Australian Dream baked into the national mythos.

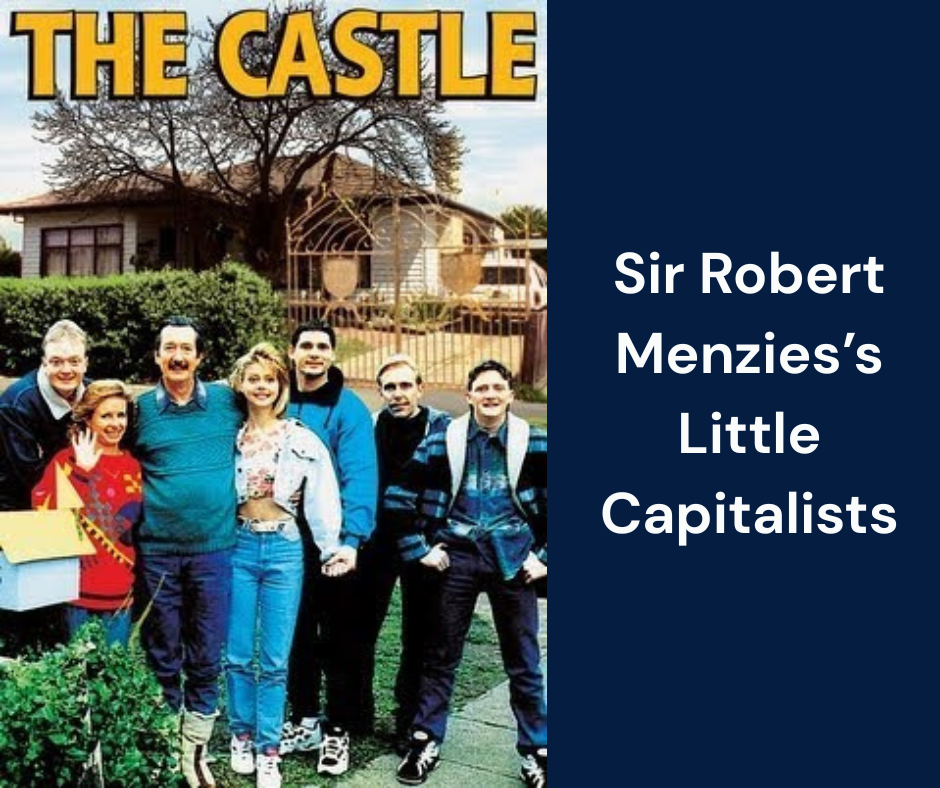

The Menzies legacy is perhaps best summed up by a line from the Australian film The Castle (1997): “Tell ’em they’re dreaming,” when malign forces try to drive an Australian everyman out of his cherished suburban castle, for the purpose of an airport expansion. Menzies in his Forgotten People broadcast considered the old saying, “the Englishman’s home is his castle,” finding the sentiment of national patriotism – in England and Australia both – as “inevitably springing from [this] instinct to defend and preserve our own homes.”

“One of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours, to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will.” The Castle’s Darryl Kerrigan, and countless others, would emphatically agree.

Labor’s postwar approach would have left our nation as stagnant as Britain – it took Margaret Thatcher’s 1980s initiative, selling council homes to residents at reduced prices to undo the mass public housing pattern established by the Atlee government’s application of the Beveridge Report. In post-Menzies Australia, the subsequent political adjustment of the Labor Party under Gough Whitlam shows the final acceptance of this legacy. Labor could only take government once they demonstrated they were no longer interested in dismantling the great Australian home ownership model that Menzies created. Having taken a wrong-turn into utopian socialism in the first half of the 20th century, the Labor movement returned to the roots of Australian radicalism, which had been so prominent in the movement to “Unlock The Lands” and secure widespread land ownership 19th century.

Yet, in the last two decades, both major parties and all levels of government have dropped the ball.

Since 1997, the proportion of private renters in Australia has risen from 20% to nearly 30%. There are of course good reasons why people might wish to rent rather than buy – geographic mobility, people partnering up but still in the early phases of family formation. There is no magic number, but enough evidence to suggest the increased difficulty in purchasing, building, and establishing a first home paints a moral policy-makers urgently need to heed.

A closer look at Menzies’ policy settings, but most importantly, the ethos which informed, guided, and inspired him, is urgently needed.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.