On this day, 24 January 1941, Robert Menzies embarks on an epic multi-leg journey to meet with Churchill and plead with him to reinforce Singapore and the Far East ahead of Japan’s looming entry into the war. It was a vital task, and one which Menzies was willing to risk both his life and his job to achieve; leaving behind a precariously balanced hung parliament and a sniping UAP party room.

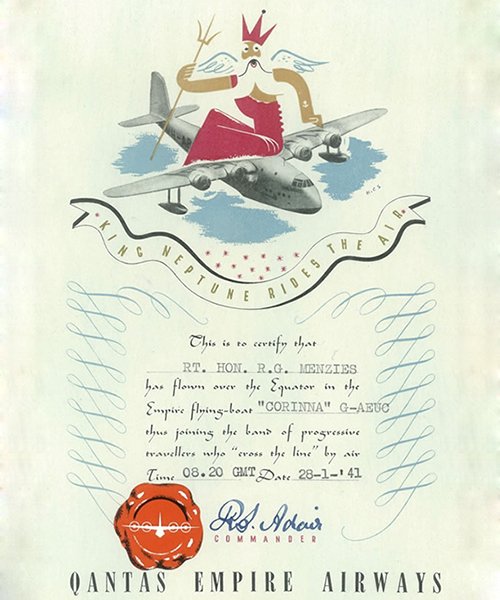

The wartime conditions meant that the trip would be perilous, and when Menzies’s wife Pattie came to see him off, she brought along her father to offer emotional support. Menzies flew via Qantas Empire flying boat to Brisbane, Gladstone, Townsville and Darwin – a clear indication of how frequently the flying boat needed to stop to refuel.

The first major international stopover was Batavia (modern day Jakarta) – along the way Menzies marveled at the rice farms he passed, ‘tiny terraced and irrigated allotments’ in which no space was wasted. Arriving at the city, he met with the Governor General of what was then the Dutch East Indies, who believed that a Japanese attack was inevitable, and assured Menzies that they would do all they could to resist any invaders, but also warned him that their resources were very limited. This was disconcerting, but Menzies nevertheless complimented the Dutch for having the foresight to transfer their government to London and continue to fight on the side of the allies – in contrast to the French who had let too many assets fall into the hands of the enemy and the Vichy regime.

The next leg saw Menzies visit the British ‘fortress’ at Singapore, and the story from the Commander in Chief Sir Robert Brooke-Popham was much the same – that his men were ready for a fight, but had less than adequate equipment and above all were ‘grievously short’ of air support. An exasperated Menzies wrote in his diary ‘Why cannot one squadron of fighters be sent out from N, Africa?’. Menzies was also concerned that he sensed that Popham was inclined towards ‘some heroic but futile Rorke’s Drift’ – a suicidal fight to the death – ‘rather than clear-cut planning, realism and science.’

There followed a series of stopovers and meetings with leaders and officials across much of Asia: Penang, Bangkok, Rangoon (now Yangon) and Calcutta. He passed Dubai, which despite its desert location was ‘quite cool at 8000 ft.’, and landed in Iraq, where Menzies was amused to hear that Australia was the chief buyer of the local date exports.

By 2 February Menzies and his travelling group had reached Palestine, where even in a brief couple of days it became apparent that there was ‘an obvious problem of reconciling Arab and Jew’ which he accurately predicted would flare up violently again once the war ended. Menzies thought that the League of Nations mandate the British held over the territory gave them responsibility without adequate power, and that they should have given it up long ago as more trouble than it was worth. But that would have been to abandon the victories won by the Australian Light Horse in the last war, members of whom Menzies paid his respects to when he visited the War Cemetary at Jerusalem. Also touching was a visit to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, where Menzies picked up a necklace for his daughter Heather.

On having his first opportunity to address Australian troops stationed once again in Palestine, Menzies was struck by the weight of it all, privately reflecting:

‘It is a moving thing to speak to thousands of young men, many mere boys, in the flower of their youth, many of whom will never see Australia again. War is an abomination of desolation, but its servants are a sight to behold. These men are unbeatable.’

Next it was on to Egypt where Menzies would be based for almost two weeks, whilst frequently venturing out on expeditions to North Africa. He met with the local Prime Minister Hussein Sirry Pasha and Australian Commander General Blamey. He spoke to more Australian troops who met him with calls of ‘How are you Bob?’, and met with hundreds of others in military hospitals who were nonetheless cheerful. He visited the British fleet (featuring several Australian ships) stationed offshore from the historic city of Alexandria, later recalling that many of the men he chatted with and even the ships he climbed aboard would not survive the war.

Then it was on to former, present and future battlegrounds at Bardia, Tobruk and Benghazi. Menzies drank wine taken from the defeated Italians, imbibing it alongside a main course of tinned spaghetti. At Benghazi, he experienced his first air raid, being woken by the explosion of bombs a few hundred yards away. He also spoke in person to the men who would soon earn fame as the ‘rats of Tobruk’, being unfortunate in having to face Hitler’s well drilled troops instead of Mussolini’s waverers – Menzies himself felt that 1 German was worth 15 Italians.

Three more legs covered Khartoum (where Robert Gordon Menzies was excited to see artefacts related to his namesake General Charles George Gordon), Lagos and Lisbon, before Menzies had to face the last and most dangerous sprint ‘running the gauntlet’. This involved flying very low under the clouds to England in the hope of avoiding being spotted by Nazi fighter planes. Finally, on 20 February, the party landed safely at Poole to be met by Australian High Commissioner Stanley Bruce.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.