On this day, 22 May 1942, Robert Menzies delivers his famous ‘Forgotten People’ radio broadcast, eloquently outlining his political vision in a manner that still resonates to this day. At the time, Menzies was only a few months removed from having to resign as wartime prime minister. In the meantime, Japan had entered the war and the unthinkable had happened with the fall of Singapore. Yet, with chaos all around him, Menzies stopped to reflect and articulate what peace should and ultimately would look like for Australia’s liberal democracy.

The broadcast began with an attack on the politics of class-warfare, something which Australian liberals had long opposed not just because they saw society as made up of individuals and families rather than groups, but also because they fundamentally opposed the representation of sectional interests in Parliament. Parliament was meant to represent all Australians, and liberals drew no distinction between the attempt to represent the ‘working class’ via caucus-controlled elected members, and the domination of a wealthy class of squatters which liberals had opposed during the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Menzies insisted that if he had to talk about class, he wanted to talk about the middle class, middling Australians who existed outside of the opposing groups of the phoney class-war, and whose main interest was their family:

‘I do not believe that the real life of this nation is to be found either in great luxury hotels and the petty gossip of so-called fashionable suburbs, or in the officialdom of organized masses. It is to be found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race. The home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health of society as a whole.’

At the heart of Menzies’s vision was the home, which gave safety and security to the family, and was an Englishman’s ‘castle’ (a concept which the classic Australian movie of that name would later pick up on). Menzies defended private property, and the Australian dream of owning a home, as the product of hard work and an inculcator of healthy instincts:

‘The material home represents the concrete expression of the habits of frugality and saving “for a home of our own”. Your advanced socialist may rage against private property even while he acquires it; but one of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours: to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will… My home is where my wife and children are. The instinct to be with them is the great instinct of civilized man; the instinct to give them a chance in life – to make them not leaners but lifters – is a noble instinct.’

Home ownership also represented moral independence; those who were able to look after and sustain themselves were the people who had the freedom to make the independent and informed choices that are so essential to the health of democracy:

‘We offer no affront – on the contrary we have nothing but the warmest human compassion – towards those whom fate has compelled to live upon the bounty of the State, when we say that the greatest element in a strong people is a fierce independence of spirit. This is the only real freedom, and it has as its corollary a brave acceptance of unclouded individual responsibility. The moment a man seeks moral and intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd, he ceases to be a human being and becomes a cipher. The home spiritual so understood is not produced by lassitude or by dependence; it is produced by self-sacrifice, by frugality and saving.’

The real driver of progress and achievement in any human society was the ambition of hard-working individuals rewarded by just incentive. Those that practised values like thrift, diligence, and duty deserved the benefits that arose from their good conduct:

‘The middle class, more than any other, provides the intelligent ambition which is the motive power of human progress… The great vice of democracy – a vice which is exacting a bitter retribution from it at this moment – is that for a generation we have been busy getting ourselves on to the list of beneficiaries and removing ourselves from the list of contributors, as if somewhere there was somebody else’s wealth and somebody else’s effort on which we could thrive. To discourage ambition, to envy success, to hate achieved superiority, to distrust independent thought, to sneer at and impute false motives to public service – these are the maladies of modern democracy, and of Australian democracy in particular. Yet ambition, effort, thinking, and readiness to serve are not only the design and objectives of self-government but are the essential conditions of its success.’

As human souls, Menzies insisted that people were of equal worth, but that nevertheless the free action of individuals had to be allowed to play out, even if that produces unequal outcomes. The alternative, in which men were levelled down and absolute equality imposed, would be a dystopian state in which the soul of man was destroyed:

‘But I do not believe that we shall come out into the over-lordship of an all-powerful State on whose benevolence we shall live, spineless and effortless – a State which will dole out bread and ideas with neatly regulated accuracy; where we shall all have our dividend without subscribing our capital; where the Government, that almost deity, will nurse us and rear us and maintain us and pension us and bury us; where we shall all be civil servants, and all presumably, since we are equal, heads of departments.’

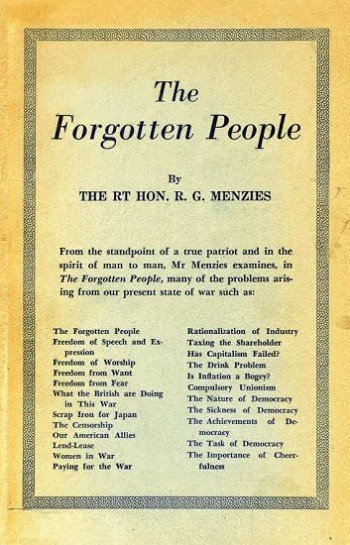

The Forgotten People was the 20th of what ended up being a series of 105 broadcasts, delivered at 9.15pm every Friday night, relayed around Australian radio stations by 2UE and 3AW between January 1942 and April 1944. Despite being one of such a multitude, it stood out immediately. It was published as a pamphlet printed the next month, and then by popular demand receiving a second print run in July 1942. The next year a book of 37 broadcasts, titled after the most famous one as The Forgotten People and Other Studies in Democracy, was also published.

The Forgotten People broadcast laid the philosophical framework for what was to become the Liberal Party of Australia, an organisation which Menzies insisted was ‘a party with a philosophy’. This was some way down the track, the UAP would face one more election before its death was finally acknowledged, but that was almost the beauty of the Forgotten People – Menzies was speaking as a backbencher with little hope of immediate power, and therefore he was free to speak with emotion and truth. Menzies was outlining his own unique vision, yet it resonated because much of what he was speaking about were already innate Australian values that he had learnt on his life’s journey from Jeparit. Menzies’s real skill lay in being able to express them perfectly.

Further Reading:

Judith Brett, Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People, (Macmillan, 1992).

David Kemp, A Liberal State: How Australians chose Liberalism over Socialism, 1926-1966 (Melbourne University Press, 2021).

Troy Bramston, Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe, 2019).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.