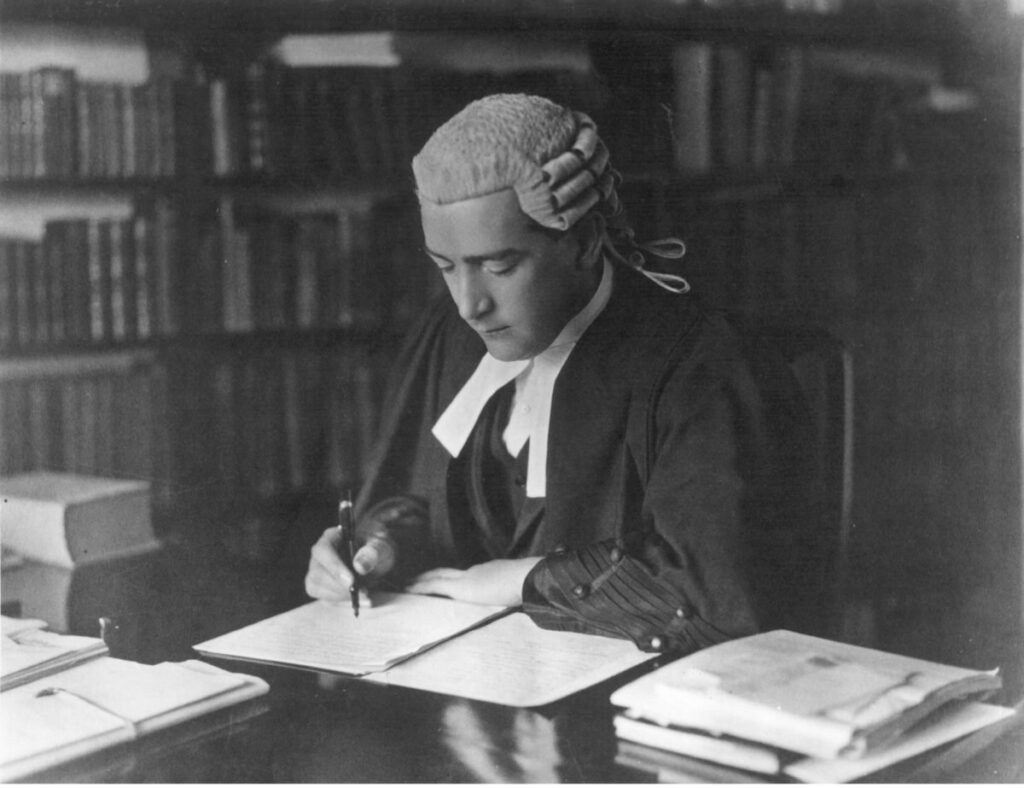

On this day, 2 May 1918, the Victorian Supreme Court votes to admit Robert Gordon Menzies to the Victorian Bar on the nomination of esteemed King’s Counsel and future Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia Owen Dixon. He would enter the Roll of Counsel as no. 155 on 13 May. After obtaining a degree from the University of Melbourne and serving 12 months of clerkship at a small conveyancing practice, Menzies was to be the very first of only three pupils that Dixon would take on at his time at the bar – a clear indication that he saw great potential in the young Robert.

Biographer Troy Bramston has documented that Menzies had dreamed of going into the law from a young age when a travelling phrenologist had visited Menzies’s Jeparit primary school, and after running his fingers over the boy’s skull, had announced definitively that Menzies would be a barrister and a public speaker. Being from a relatively modest family, this was something that Menzies would need to win a number of scholarships to have any hope of accomplishing, but ultimately his combination of talent, effort, and clarity of objective ensured that every such barrier would be overcome.

Menzies’s arrival onto the Victorian legal scene had been heralded in The Age’s legal notices on 13 April 1918, in which he had paid for an announcement stating:

‘To the Supreme Court. To the Board of Examiners, I Robert Gordon Menzies, formerly of “Lowan” Rockley-Road South Yarra, in the State of Victoria, but now of No. 83 Wellington Street, Kew, in the said State, Bachelor of Laws of the University of Melbourne and articled clerk, hereby give notice that I intend to apply on the first day of the May sittings of the Full Court to be admitted to practise as a barrister and solicitor of this honourable court.’

Menzies would later recall that his times spent as a young lawyer were some of the happiest days of his life – even though he was then averaging an 80 hour work-week. In Dixon, the energetic and ambitious young man had the perfect mentor, who he would later describe as ‘the greatest legal advocate I saw either here or abroad’. On one occasion Menzies would recall when his wife Pattie had questioned some opinion that Menzies had offered, to which he replied, ‘Well, Dixon thinks so, and that’s good enough for me’. Pattie then said in exasperation ‘Bob, I think you ought to realise that Dixon is not God!’, to which Menzies replied, ‘You’re quite right, my dear; but only just’.

Within four months of his admission, Menzies would first appear at the High Court as Dixon’s junior counsel – something he would do in more than a dozen cases both there and at the Supreme Court of Victoria. By 1919 he was already appearing unled before the High Court, by 1920 he had won a landmark constitutional decision in the Engineers’ Case, and by 1929 he would be given the honour of becoming Australia’s youngest ever King’s Counsel.

By then of course, Menzies had entered politics, but he did so out of a sense of public duty, and certainly not because he preferred the political game to the law, which he insisted always remained his first love. Indeed, for much of the 1930s Menzies managed to mix the two by serving as Attorney General first for the State of Victoria and then federally. He even got to travel to London, appearing in numerous cases before the Privy Council, and being admitted to Gray’s Inn – one of the city’s ancient and prestigious inns of court.

For much of his career in politics there loomed the possibility that Menzies would exit to take up a judicial posting, and this particularly seemed to be the case when he had to resign from the prime ministership in late 1941. However, by the time Menzies did finally leave politics in 1966 he did not have the energy to take up such an arduous position, expressing that he had ‘no ambition to knock off work to carry bricks’.

The idea of law being laborious was something of a divergence from a statement he made in 1954, when Menzies suggested that ‘a man like myself who loves the law, and the practice of the law, and the whole philosophy of the law, would [not] go into this turbulent stream, for a job.’

For Menzies, both law and politics were ultimately vocations, in which he felt compelled to strive and to achieve something greater than mere pecuniary return. Menzies had an almost religious faith in the power of the Common Law, which he believed had evolved over centuries to protect the rights of the individual through the accumulated wisdom of precedent. Indeed, he went so far as to declare that ‘To live in a Common Law country is, in itself, the very best guarantee of the rights of the individual’. He also maintained that ‘the law’s greatest benefits are for the minority man – the individual’, and that instinct to protect people from majority tyranny and the arbitrary whims of the state played a powerful role in informing Menzies’s political liberalism.

Further Reading:

James Edelman and Angela Kittikhoun, ‘Menzies and the Law’, in The Young Menzies, ed. Zachary Gorman, (Melbourne University Press, 2022).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.