On this day, 11 November 1965, Robert Menzies introduces two Constitutional Alteration Bills into Parliament – laying the foundation of what would become the famous 1967 referendum. That poll would involve three constitutional changes bundled into two referendum questions, including giving the Federal Government the power to make special laws for Indigenous Australians under the ‘race power’ of Section 51 (xxvi) from which they were initially explicitly excluded. This was not included in Menzies’s original proposal as he believed that the existing Constitutional provision acted as ‘a protection against discrimination by the Commonwealth Parliament in respect of Aborigines’ and that there was an ‘attractive argument’ to be made in favour of removing the race power altogether. He did support the other aspect of changing the Constitution to include Indigenous people in population counts, declaring that ‘section 127 is completely out of harmony with our national attitudes and with the elevation of the Aborigines into the ranks of citizenship which we all wish to see’ – and this would be vindicated by the overwhelming 90.77% ‘yes’ vote.

While the Indigenous issue is paramount in the popular memory, it may be argued that Menzies’s primary interest in what became the 1967 referenda was instead the oft-forgotten and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to remove the ‘nexus clause’ which insists that ‘The House of Representatives shall be composed of members directly chosen by the people of the Commonwealth, and the number of such members shall be, as nearly as practicable, twice the number of the Senators’. This means that you cannot increase the number of House members without increasing the number of Senators, and in practice has meant that Australian governments have been extremely reluctant to increase the size of Parliament even as our population grows and electorates swell to bloated sizes that defy the stated premise of forming ‘communities of interest’.

The nexus clause’s inclusion in the Constitution has a complicated history. Almost all of the Constitution’s provisions were modelled on existing precedents of political systems from around the world, with the exception of the nexus, which was a reluctant innovation born out of a perceived conflict between American-style federalism and British-style responsible government. Many of the circumstances in which the nexus was conceived never eventuated; not only did the Senate quickly become a party House rather than a true States’ House, but Australia’s founding fathers thought that there would likely be new States which would increase the Senate (and therefore the House of Representatives) without increasing the number of Senators for each individual State.

Menzies had long been an advocate of increasing the size of Parliament, having argued in a ‘Forgotten People’ Broadcast from 1943 that the move was necessary because:

- There were too few members to choose a healthy Cabinet from, ‘After all, a much better cricket team can be chosen from Australia than from Randwick’.

- That because of this it was ‘not so much a distinction to be included in a Cabinet as a slight to be omitted… [producing] too many issues in Parliament which are personal rather than broadly political’.

- ‘In a small Parliament a small group or even one or two men can hold the balance of power, can really nullify large masses of voting power, and can bring government down from the level of principle to that of bargain’.

- That electorates were far too large not just in terms of population but also territory, meaning that it was harder for MPs to administer their whole electorate and harder for electors to get in contact with their MP. The time involved in serving so many people also meant there was less room to ‘devote a proper proportion of [a Member’s] time to really National and international questions’.

In 1949 the Parliament did significantly increase for the first time in Commonwealth history, as each State went from having six Senators to having ten and the House of Representatives grew in a corresponding fashion. However, with the post-war immigration and baby boom this increase was rapidly offset by rising population, and Menzies did not want to have to arbitrarily increase the size of the Senate to rectify the issue, particularly as high levels of immigration would presumably continue indefinitely (as indeed they have). He was also of the belief that you needed to have an uneven number of Senators going up for election at each half-Senate cycle, or else proportional representation would mean that outside of a landslide Labor and the Coalition were likely to win the same number of seats and things would be deadlocked, so each State having twelve Senators (as is now the case) was ruled out.

The Constitutional Alteration Bills both passed the Parliament, but they were ultimately allowed to lapse because Menzies retired in January 1966 and Harold Holt did not want to hold a referendum so early after coming into office and he had also expressed some scepticism about the need to increase the size of Parliament. But after winning the 1966 election in landslide fashion, he decided to pick up the proposals and reintroduce them with the race power addition.

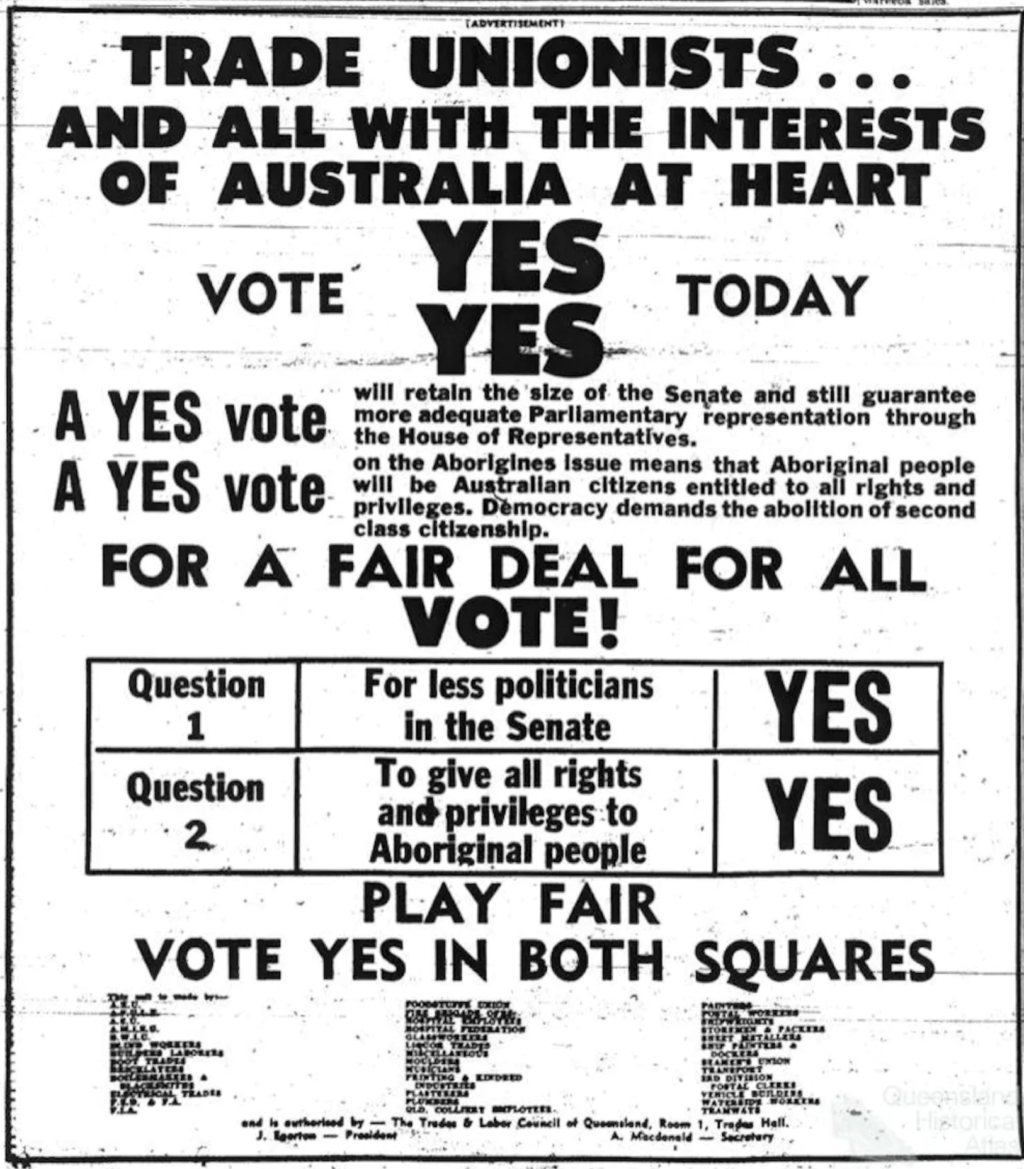

In the subsequent campaign both the Government and Opposition supported a ‘yes’ vote on the nexus abolition, while a small but determined ‘no’ campaign argued that Australia was already over-governed and did not need any more politicians, which they believed would be the inevitable result of making it easier to increase the size of Parliament. The ‘yes’ campaign tried to counter by arguing that a ‘no’ vote would create more politicians by requiring more Senators, but the simplicity of the ‘no’ case won the day, securing the backing of five States and 59.75% of Australians. The result has been an important factor in ensuring that Parliament has not grown since 1984, particularly as since the rise of Senate minor parties the majors have become particularly reluctant to increase Senate numbers and therefore lower the quota required to get a member up (the effects of which were seen in the 2016 double dissolution).

Further Reading:

Zachary Gorman & Greg Melleuish, ‘The nexus clause: A peculiarly Australian obstacle’, Cogent Arts & Humanities, 2018, Full article: The nexus clause: A peculiarly Australian obstacle (tandfonline.com)

Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Debates, 11 November 1965 :: Historic Hansard

Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus, The 1967 Referendum: Race, Power and the Australian Constitution (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.