On this day, 30 November 1963, Robert Menzies is re-elected as Prime Minister for the seventh consecutive and final time. The election victory gives Menzies a virtually unassailable lead as Australia’s longest tenured leader and gives him the opportunity to do what no other Prime Minister has done, exit of their own free will and on their own terms.

This was the first election since a 1962 amendment to the Commonwealth Electoral Act had overturned a ban on Indigenous Australians voting for Federal elections in Queensland and Western Australia. This was consequently the first election in which all Indigenous Australians of voting age were allowed to vote, though it should be noted that their enrolment was not compulsory and there were still many obstacles when it came to exercising the franchise, particularly for those in remote communities.

In 1961 the backlash from a credit squeeze had seen the Menzies Government almost lose office, as the Prime Minister was forced to rely on a single seat majority after the election of the Speaker. Two years later, after almost 14 years in office, there was a sense that the Government had exhausted its agenda and was growing stale.

This sense of agedness was addressed in Menzies’s policy speech, which insisted that it was not time for change for change’s sake. After such a long period of rule, Menzies even had to try to explain to younger voters what life had been like before the transformations wrought by the Menzies era and under ‘the Labour Party Socialist era of restrictions, attempted nationalisation, and the discouragement of enterprise’.

Despite this perceived fatigue, Menzies was able to reinvigorate his Government by picking up the issue of state aid for non-government schools, particularly poor Catholic schools, as an innovation which could tangibly improve the lives of thousands of families. The issue had been brought to national attention by the famous Goulburn Catholic School ‘strike’ of 1962, which demonstrated that the public school system would be overwhelmed if the private system was not given enough money to keep itself afloat.

In his policy speech Menzies announced the introduction of 10,000 Commonwealth scholarships for secondary students, regardless of the schools they attended, and ‘£5 million per annum for the provision of building and equipment facilities for science teaching in secondary schools. The amount will be distributed on a school population basis, and will be available to all secondary schools, Government or independent, without discrimination’.

In adopting this policy position Menzies was helping to dismantle deep sectarian divisions in Australian society, divisions which he had long opposed. He was also helping to facilitate the movement of Australian Catholic voters, who had once been deeply wedded to the Australian Labor movement, over to the Coalition, a process that had arguably begun with the Great Labor Split and the formation of the DLP. For its part, the Labor Party was incredibly divided over the state aid issue, particularly as the split had ignited fierce sectarian tensions within the organisation.

The other major electoral commitment was in the field of housing policy. This included a new-home purchase scheme, and an initiative that would help to increase the availability of housing loans.

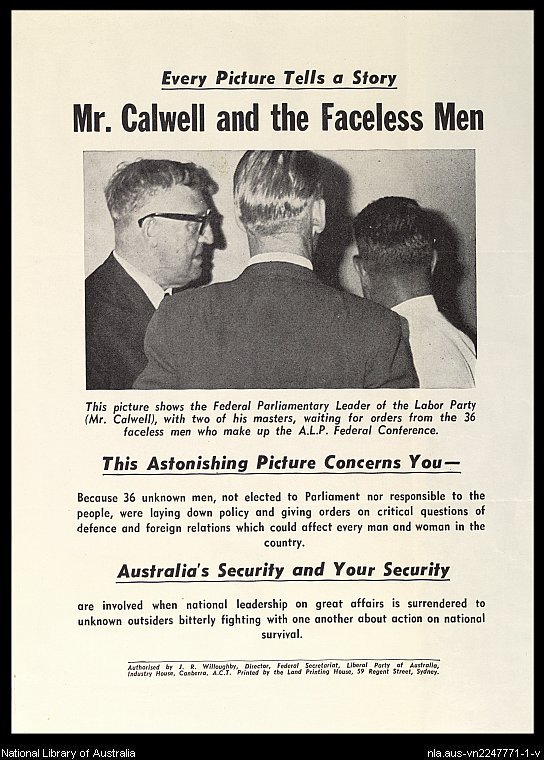

While Menzies was having a hard time convincing young voters of the flaws of a Labor governance they had never experienced, he was given a golden opportunity to discredit his opponents with the characterisation of the ‘faceless men’ of the Labor Party. Coined by journalist Alan Reid, the phrase referred to a famous photograph of Opposition Leader Arthur Calwell and his Deputy Gough Whitlam standing outside the Kingston Hotel in Canberra, waiting for the ALP Federal Conference to decide on the Opposition’s policy for the upcoming election. Reid used the photograph as the basis for a scathing critique of the Labor leadership in Sydney’s Daily Telegraph.

The phrase was evocative of a deep philosophical divide in the Australian party system. Australian Liberals had long been opposed to Labor’s ‘caucus pledge’, which forced members to vote as the caucus compelled them or be expelled, as an attack on individual conscience and the parliamentary system of government. Indeed, Judith Brett has argued that the pledge was the main basis for the fusion between George Reid’s Free Trade Party and Alfred Deakin’s Protectionists, two groups who had previously clashed over their contrasting visions of what ‘liberalism’ meant. It is worth noting that Joseph Cook, the first ‘Liberal’ leader to win a Federal election in their own right, had been a leader of the NSW Labor Party in the 1890s before leaving over the introduction of the pledge.

Menzies, who was a fervent believer in the Burkean idea that members were required to independently evaluate issues based on their own reasoning, such that he had more than once resigned from a ministry over a point of principle, seized upon Reid’s phrase. He denounced the ‘thirty-six “faceless men”, whose qualifications are unknown, who have no elected responsibility to you’ for co-opting a power which was not rightfully theirs. The suggestion was that the whole system of democratic accountability broke down if those outside of Parliament, rather than its elected members, were making the key decisions which dictated Australia’s future.

This devastating critique combined with the state aid policy and improving economic conditions proved to be a winning formula, though the assassination of American President John F. Kennedy, which occurred a week out from the poll and may have encouraged voters to err on the side of stability, also played a role. The Government achieved a 3.1% positive swing and picked up 10 seats, a result which would spell the end of Arthur Calwell’s stint as Labor Leader.

Further Reading:

A.W. Martin, Robert Menzies, A Life Volume 2 1944-1978 (Melbourne University Press, 1999).

Robert Menzies, Policy Speech, 12 November 1963, Museum of Australian Democracy, available at https://electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au/speeches/1963-robert-menzies

Troy Bramston, Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe, 2019).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.