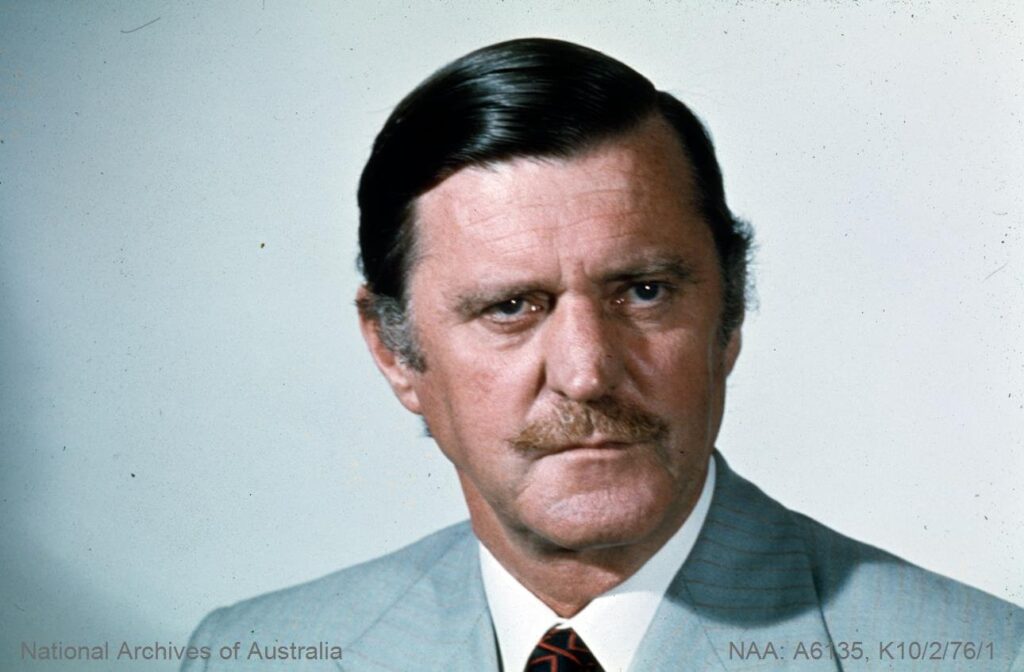

On this day, 9 December 1961, Robert Menzies narrowly holds on to office after a large swing against his incumbent government. The Coalition is left holding just two seats more than the Labor Opposition, meaning that after the election of a Speaker Menzies must rely upon a razor thin one seat majority.

The result was largely a product of the ‘credit squeeze’ which had rocked the Australian economy. In brief, the long-term prosperity that Menzies had achieved by the late 1950s led to a decision to end the illiberal system of import licensing, a move justified on the grounds that it would help to combat inflation by promoting competition. However, in a nation where consumers had long had their choices restricted by protectionism, pent up demand meant this freedom led to a surge of imports that exceeded all expectations, and which undermined Australia’s balance of payments and reserves of U.S. dollars. The Government then over-corrected, producing a drastic deflationary budget that increased taxes and restricted bank loans. The result was a minor recession which saw some businesses default and unemployment rise to 3.5%, an aberration in a post-war era that had grown accustomed to ‘full employment’.

Despite growing press criticism throughout 1961, Menzies decided to stay the course and wait for conditions to correct themselves. After more than a decade in government and with the electoral security provided by the aftermath of the Great Labor Split, Menzies had arguably grown complacent. He told a confidant that ‘I do not think that we will be beaten. There are no circumstances which would suggest even a remote possibility of the Opposition winning 17 seats… I think that the electors will hesitate to entrust their fortunes to the most divided and leaderless Opposition I have ever seen’.

The Government campaigned on its record, promising a return to prosperity and heavy investment in a mining sector which was on the verge of a boom. Under Arthur Calwell, Labor tried to place the issue of unemployment at the centre of the contest, proposing selective import controls, increased tariffs, and greatly expanded public services. The latter allowed Menzies to claim that his opponents would either reignite inflation or have to further increase taxes.

The election saw the Government openly criticised by business interests who could normally be relied upon to support it, particularly in the manufacturing industry which had a vested interest in blocking competitive imports. If anything this made Menzies defiant, as he insisted that short term pain for long term gain was the course of action that the national interest, rather than sectional interests, required.

Meanwhile, for the first time ever Warwick Fairfax’s Sydney Morning Herald told its readers to vote for Labor, in an editorial which insisted that the paper ‘stands today as it had throughout its history for liberal principles’ but that the Government had abandoned those principles by turning ‘more and more to bureaucratic planning and socialistic methods’. More extraordinary still, some of the staff of the SMH and the associated Australian Financial Review even became directly involved in Calwell’s campaign, doing things like writing speeches and having input on policy.

This support helped Labor to gain several seats in NSW, but the swings against the Government were most pronounced in Queensland, with a long and drawn-out count in the seat of Moreton left to decide whether there would be a hung Parliament. The Coalition was undoubtedly saved by DLP preferences, as Labor received 5% more of the primary vote and is even estimated to have won the overall two-party-preferred 50.5% to 49.5%. Labor won 15 seats, just shy of the 17 which had been so unthinkable to the Prime Minister.

The result was a reality check for Menzies who, after fuming against the actions of the Fairfax press, was able to recompose himself and lead what proved to be a remarkably stable government despite the one seat majority. Many thought that the narrow result might have led Menzies, who would turn 67 just as the extended vote count finished, to retire. However, if anything it seems to have compelled him to serve out the term and seek re-election so that he could exit politics as a winner and leave his successor in a favourable position, which is precisely what happened.

Further Reading:

A.W. Martin, Robert Menzies, A Life Volume 2 1944-1978 (Melbourne University Press, 1999).

David Lee, ‘Issues that swung elections: the “credit squeeze” that nearly swept Menzies from power in 1961’, The Conversation, 30 April 2019, https://theconversation.com/issues-that-swung-elections-the-credit-squeeze-that-nearly-swept-menzies-from-power-in-1961-115140

Troy Bramston, Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe, 2019).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.