On this day, 29 May 1954, Robert Menzies’s Coalition Government narrowly fights off the challenge of the Labor Party led by Dr H.V. Evatt to win its third term. Though this election is generally remembered for taking place in the aftermath of the shock Petrov defection, the main campaign issue was arguably Labor’s big spending program and its potential economic consequences. After the election, Menzies would boast that ‘the Australian electors were offered Father Christmas and came to the conclusion that he was a burglar with a false beard’.

The 1954 election was the second re-election campaign for the Menzies Government, but it essentially functioned as its first real test. That was because the 1951 double dissolution election had been called early in response to Labor’s repeated obstruction in the Senate, and so it was fought on a re-hash of many of the same issues that had brought the Coalition to power in 1949. Even the defeated Labor leader Ben Chifley stuck around for an attempt to regain the Prime Ministership, something which has since been extremely rare in Australian politics.

In 1954, the electorate would get to judge the Coalition over its performance over almost four and a half years of government. This had not always been smooth sailing, with notable hiccups including the ‘horror budget’ delivered in response to inflationary pressures in 1951, and the defeat of the referendum held to ban the Communist Party that same year.

Meanwhile, Labor had a new leader with an impressive resume which included success as a High Court Justice and even a stint as President of the United Nations General Assembly. Evatt made an ambitious range of un-costed election promises including the abolition of means tests on old age pensions, an immediate increase in the rates of other benefits, cheap housing loans through the Commonwealth Bank, and a version of universal health insurance.

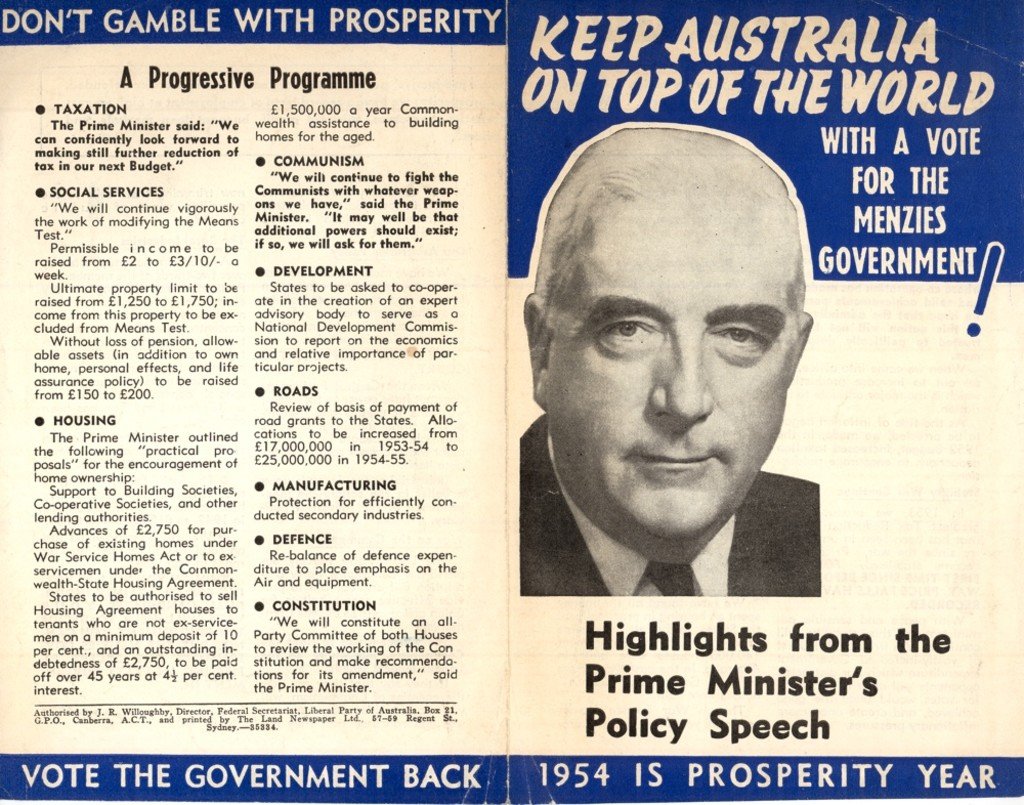

In response, Menzies took aim at the extravagant spending as ‘the deadliest attack on the stability of Australia’. In his policy speech Menzies stood by the government’s record, particularly on the economy which had recovered from the issues that induced the horror budget and was now enjoying the prosperity for which the ‘Menzies era’ is widely known:

‘We hand back to your custody as voters a nation more prosperous, more productive, possessed of more social justice, better defended, and with more friends abroad, than ever before. We present our accounts, not with apology and anxious explanations, but with pride.’

Menzies highlighted the Government’s rigorous program of public works, success in increasing rates of home ownership, and reduction of taxes which had spiked in 1951. Menzies would increase social spending like the Opposition, but not with the same profligacy – the means test on the old age pension, for example, was to be modified rather than abolished. He also reiterated the philosophical divide between liberalism and the ‘socialism’ of his opponents, a differentiation which had been important in his winning office in 1949:

‘We believe in the individual, in his freedom, in his ambition, in his dignity. If he becomes submerged in the mass, and loses his personal significance, we have tyranny. And because of this, we believe in free enterprise; not enterprise free of social obligation, but free enterprise in the sense that it embraces free choice, reward for effort and skill, encouragement to grow and be self-reliant, and strong. We believe that, as every individual has his significance and his rights, sectional policies are wrong. We believe in the growth of this nation. We believe that this requires more people, more industries, profitable employment and investment alike, enterprise, the immortal pioneering spirit.

The Socialists do not really believe in these things. Their ideas may work somewhere, but in a country like ours, which needs the spirit of risk-taking, of dynamic energy, the dull, unproductive Socialist philosophy is merely the definition of stagnation and death. Here we have a conflict both far-reaching and vital. The Socialists say that we all ought to work for a Government Department; that we don’t need to be encouraged to work in any case, because an all-powerful Government will provide. In Australia the Socialists—who call themselves Labour—carry their ideas to the most cynical extremes.’

The election result saw Labor win a majority of the primary vote, though notably there were six coalition seats which went uncontested and therefore provided no voter tallies. However, Labor lost the overall election by seven seats because their support was concentrated in ‘dead red’ areas while that of the Coalition was more spread out.

Evatt would famously come to blame the narrow election loss on the Petrov affair, but at the time the Royal Commission on Espionage had bipartisan support, and its most damning revelation, that members of Evatt’s own staff had been compromised, would not surface until after the election. Menzies was principled enough to impose a ‘gag’ on Liberal members talking about Petrov during the campaign, though it was not universally observed, and he still attempted to paint Labor as being ‘soft’ on communism for its opposition to the referendum.

Dr Bridget Brooklyn, who wrote a book chapter examining the impact of the Petrov affair on the 1954 result, argues that it was domestic issues and a desire for stability which mattered more than any communist bogey. In an early example of a ‘presidential’ race, Menzies’s image as a steady hand at the wheel won out over the erraticism of Evatt who was dogged by divisions which were evident in Labor even before its later split. Brooklyn concludes:

‘Australian democracy – unique and far more vibrant than it is normally given credit for – nevertheless has a tendency toward conservatism in the literal meaning of the word. In 1954, this conservatism included the habit of opting for the status quo rather than for drastic measures when it came to weeding out Communists. What matters about the 1954 election is its demonstration that Australian political decisions are not made in extremis, but more with regard to the material comforts and sense of stability that consistently appeal to the Australian voter. These were things that Menzies – much more than the febrile Evatt and his increasingly troubled party – could offer.’

Further reading:

Brooklyn, B. ‘1954: did Petrov matter?’ in B. T. Jones, F. Bongiorno, & J. Uhr (Eds.), Elections Matter: Ten Federal Elections that Shaped Australia (Monash University Publishing, 2018)

David Kemp, A Liberal State: How Australians chose Liberalism over Socialism, 1926-1966 (Melbourne University Press, 2021).

Robert Menzies, ‘Policy Speech’, Delivered at Canterbury Victoria, 5 May 1954, Election Speeches · Robert Menzies, 1954 · Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House (moadoph.gov.au)

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.