On this day, 21 August 1943, the incumbent Curtin Labor Minority Government trounces a Coalition Opposition led by Country Party Leader Arthur Fadden at a general election. The severe election defeat would precipitate the dissolution of the United Australia Party, and ultimately the formation of the Liberal Party of Australia.

It is a remarkable fact of Australian political history that such has been the dominance and consequent expectations of success for centre-right parties that both the Nationalists and the United Australia Party only ever lost one election before they were replaced with a new entity (though admittedly the 1940 election had resulted in a hung Parliament rather than a clear-cut victory for the latter). Both parties were formed in response to a national crisis, the First World War for the Nationalists and the Great Depression for the UAP, and eventually exhausted their premises as circumstances evolved.

The UAP was in some respects defunct even before the 1943 election was held, as it did not have the strength and pride to take up its position as the leading Coalition party, instead relegating itself to submission to a Country Party Opposition Leader in the aftermath of the short-lived Fadden Government. Indeed, Menzies had resigned the leadership of the UAP specifically because of this topsy-turvy Coalition arrangement, and when he set up the National Service Group to try to reinvigorate the UAP one of his main complaints was that his successor as party leader, the aged Billy Hughes, seldom held stand-alone party meetings beyond the joint Opposition meetings with the Country Party.

The NSG had been formed around a matter of principle very dear to Menzies, namely that if Australia was going to benefit from the efforts of American conscripts serving in our region, then it had a moral duty to remove restrictions on where its own conscripts could be sent. But it led to a public spat between Menzies and Hughes that was played out on national radio broadcasts and this open division placed the UAP in a very precarious position when the Government called an election two-months before it was constitutionally due.

The NSG represented a response to a fundamental dilemma, which was how to act as an Opposition during wartime. It was easy for the Government to accuse a critic of causing divisions and acting to undermine the war effort, while there were even problems with censorship. As prime minister, Menzies had repeatedly offered Labor the chance to form a national government in conjunction with the Coalition to fully eliminate such divisions, even offering at one stage for Labor to lead it. Labor had repeatedly refused, but now in Government it was happy to have its cake and eat it as far as demonising political opponents for being divisive. Hughes and a section of the UAP were happy to let Labor govern with little restraint, whereas the NSG thought that the duty to hold the Government to account had not been alleviated by circumstance.

The Opposition’s election campaign centred around an uninhibited pursuit of victory, attacking Labor for failing to curtail devastating wartime strikes, and for using wartime government as an opportunity to pursue socialisation. In his policy speech for the Opposition, Fadden added a novel proposal, outlining a system of post-war credits with a specific promise that one-third of all income tax (a tax which had increased greatly to fund the war-effort) collected after June 30 1942 would be repaid in cash by instalments when the war was over. Menzies was quick to rebut this proposal as inflationary, telling the electors of Kooyong:

‘Complete honesty requires that I should say that I cannot subscribe to that proposal. We need every shilling that can be obtained from the Australian people to win the war.’

This prompted Fadden to accuse Menzies of stabbing him in the back, and destroyed any sense of momentum the Opposition may have gotten from the policy announcement. The election campaign took a serious personal toll on Menzies, who had to repeatedly defend himself against the sordid and entirely fallacious ‘Brisbane Line’ controversy, and who was quite hurt that Curtin, whom he otherwise respected, did not do enough to stamp out the flagrant lie. Curtin was also able to take credit for many major achievements as far as wartime production and organisation, that had actually been initiated by the Menzies Government but which naturally had a time-lag before they bore fruit under his fortuitous successor; all while Labor denigrated Menzies’s record of leadership and accused him of being defeatist. In one poignant moment of honesty, an exasperated Menzies told a radio audience ‘I have regard for my reputation…it will be the only real asset I shall leave to my children, and I’m not going to leave it smeared without a battle’.

There was also the issue of organisational splintering, with nascent rival centre-right organisations such as the Services and Citizens Party in Victoria, the Liberal-Democratic and Commonwealth parties in NSW and the Queensland Peoples Party, running against the UAP alongside many unendorsed UAP supporters who served to split the Opposition’s vote. Menzies publicly admitted that ‘I am convinced that there must be great rejoicing at Labour headquarters at the hopeless confusion which is being set up in the non-Labour ranks’.

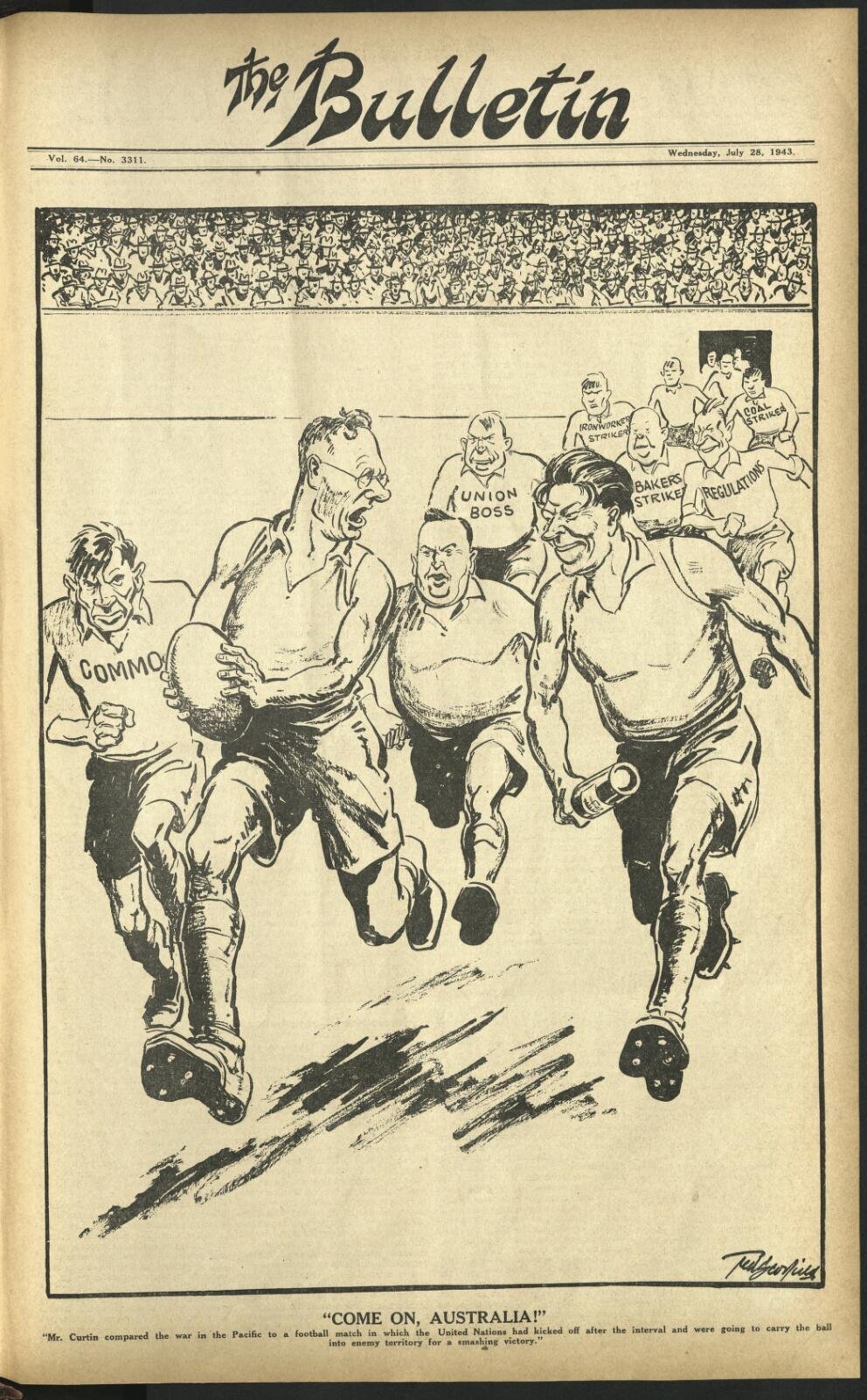

Despite all the severe divisions in the Opposition and the natural inclination of the electorate to want continuity during the war, few people saw the election result coming, and even Curtin is said to have had significant doubts. The strikes in particular were expected to have an impact, seeing as they represented such an utter betrayal of the war effort and Australia’s fighting men, Labor were so closely linked with the union movement, and the Attorney General had even arranged to drop charges laid against militant union officials.

In the end, Labor won 49 of the 74 seats, giving it a clear majority in the House of Representatives for the first time since 1929. Results in the Senate, which was then elected without proportional representation allowing winners to ‘take all’, were even more devastating. The Labor Party won in all States gaining 19 Senators and giving it a majority from 1 July 1944 which represented the first ALP Senate majority since 1914.

When trying to piece together what had happened, Menzies cited the personal popularity of the prime minister, the:

‘concerted and well-organised concentration of Labour’s campaign around one leader and one cause of the divisions in the Opposition, the honest but unfortunate difference in Opposition policy, and the debilitated condition of the Opposition organisations which for the most part were hurriedly got up for election purposes. It is clear that much rebuilding must take place if true liberal democracy is to continue as a dynamic force in Australian politics. Thousands of Opposition supporters must get rid of the idea that elections can be won at the last moment. If the Opposition campaign of 1946 is to be won it must begin today’.

Preparations did begin in earnest, and within a couple of months Menzies was prophesising what he dubbed ‘a liberal revival’. ‘If I may adopt one of the Prime Minister’s football metaphors – the Opposition is heavily down at half time, but if it learns the lessons of the play so far it can still win the game’.

Further Reading:

Sylvia Marchant, ‘Things Fall Apart: The End of the United Australia Party 1939 to 1943’, ANU Masters Thesis, 2018, Masters_Marchant-ThingsfallaparttheendoftheUAP.pdf (anu.edu.au)

A.W. Martin, Robert Menzies, A Life: Volume 1 1894-1943 (Melbourne University Press, 1993).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.