On this day, 6 March 1937, the Australian people vote on two separate constitutional amendments: whether to give the federal government the power to legislate on air navigation and aircraft, and whether to give it the power to collectively market primary produce.

The Australian Commonwealth came into being on 1 January 1901, almost three years before the Wright brothers took their landmark 12 second flight above the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk North Carolina. While hot air balloons were already in existence, they were far from numerous or consequential enough to have come up in the discussions which drew up Australia’s Constitution. Consequently, no power to legislate on air travel was ever included in the document, and in line with the federal principle of ‘residual powers’, any power not explicitly given to the Commonwealth was said to reside with the States.

Nevertheless, when in 1920 the Federal Parliament passed an Aircraft Navigation Act, in response to the rapid expansion of aeroplanes which had be fueled by the Great War, little fuss was made. That was until 1936, when an incident involving a controversial pilot named Henry Goya Henry garnered national attention. Henry already had a chequered record in a cockpit, having crashed a monoplane at Manly in July 1930, killing his only onboard passenger and resulting in Henry himself losing one of his legs.

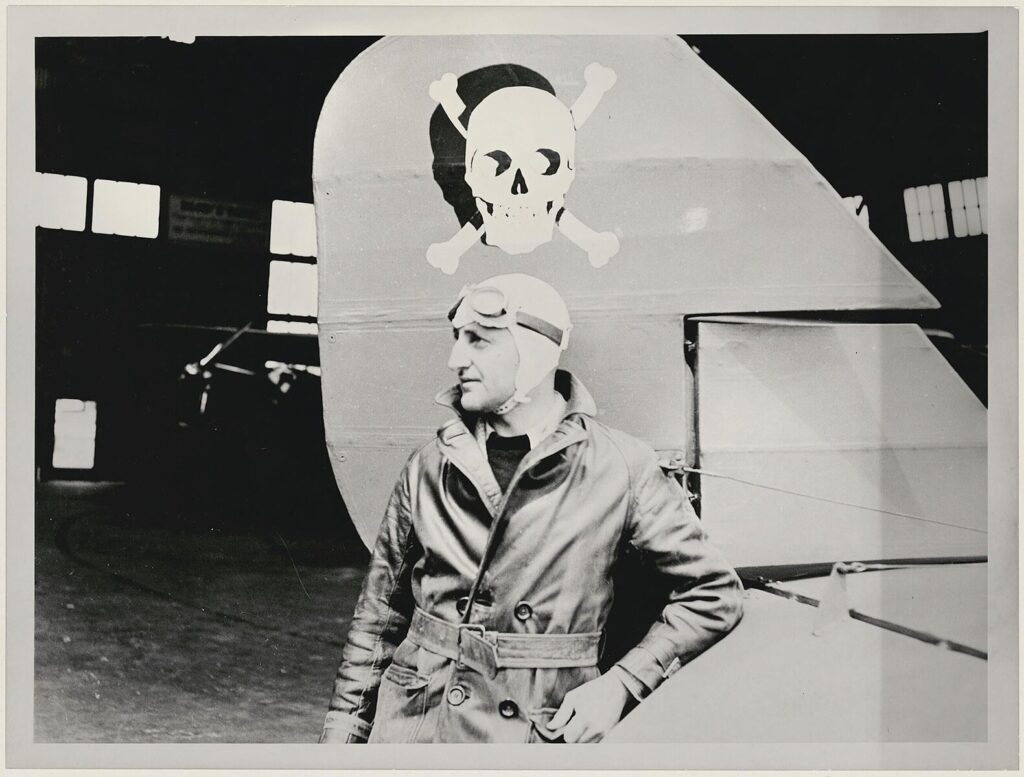

Unperturbed, Henry got a prosthetic replacement and continued to fly first in Air Taxi, and later in a biplane in which he took people on joy rides. In the latter role, he frequently flouted the federal government’s air navigation regulations, leading to his license being suspended. Henry repeatedly ignored such suspensions, and kept on flying anyway, until a spectacular and completely unauthorised flight under the Sydney Harbour Bridge brought matters to a head.

Facing a serious prosecution, Henry sought the advice of his brother Alfred, who happened to be a solicitor. Alfred pointed out that the regulations his brother had violated may well be unconstitutional, leading to a High Court Case which found that indeed they were.

With the whole regulatory framework underpinning what had become a major industry thus completely undermined, the Federal Government quickly resolved to go to a referendum to restore order in the air. They simultaneously sought to restore their power to impose coordinated schemes for the marketing of primary produce, which had likewise been deemed unconstitutional in a ‘Dried Fruits’ case that Menzies himself had lost before the Privy Council.

As Attorney General Menzies was charged with leading the ‘Yes’ campaign, something he would later describe as one of the labours of Hercules. His argument in the case of marketing was that the High Court had already made it clear that the states could not legislate on interstate trade, so if the Commonwealth could not in this instance nobody could. As for aviation, Menzies thought that this was ‘ludicrous’ to leave to the states given that the very nature of the technology meant that it covered vast distances.

In both instances the ‘No’ cases argued that the changes could lead to government-controlled monopolies (or even a British owned airline trust) which would raise the price of primary produce and air travel. For air travel the argument was also made that a federal airline might out-compete state railways, thus bankrupting the states who were still highly reliant on railway revenue to remain solvent, as well as harming the rural communities which relied on the railway network.

The Labor Opposition had a foot in each camp, opposing the marketing change (which was essentially in the Country Party’s self-interest) but supporting the aviation one. While marketing was thus doomed from the start, even bipartisan support was not enough to get aviation over the line, as it was heavily defeated in the three smaller states as well as more narrowly in New South Wales. Notably, the support was very strong in Victoria and Queensland, such that Yes won the overall vote with 53.6% in favour.

Like in so many other cases, the High Court has since defied the expressed will of the Australian people (or at least 4 States) by expanding the power of the Commonwealth through changing its interpretation of the Constitution. The Court now maintains that the External Affairs power gives the Federal Government regulatory powers over aviation, since it has the power to make international treaties, some of which involve air safety.

As for Henry, although he had thwarted the Federal Government, he did not get to savour his victory, for he soon went bankrupt. Nevertheless, the whole affair won him a level of enduring fame. Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum has even bought his infamous biplane the ‘Jolly Roger’, which has been preserved as a unique piece of both aviation and constitutional history.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.