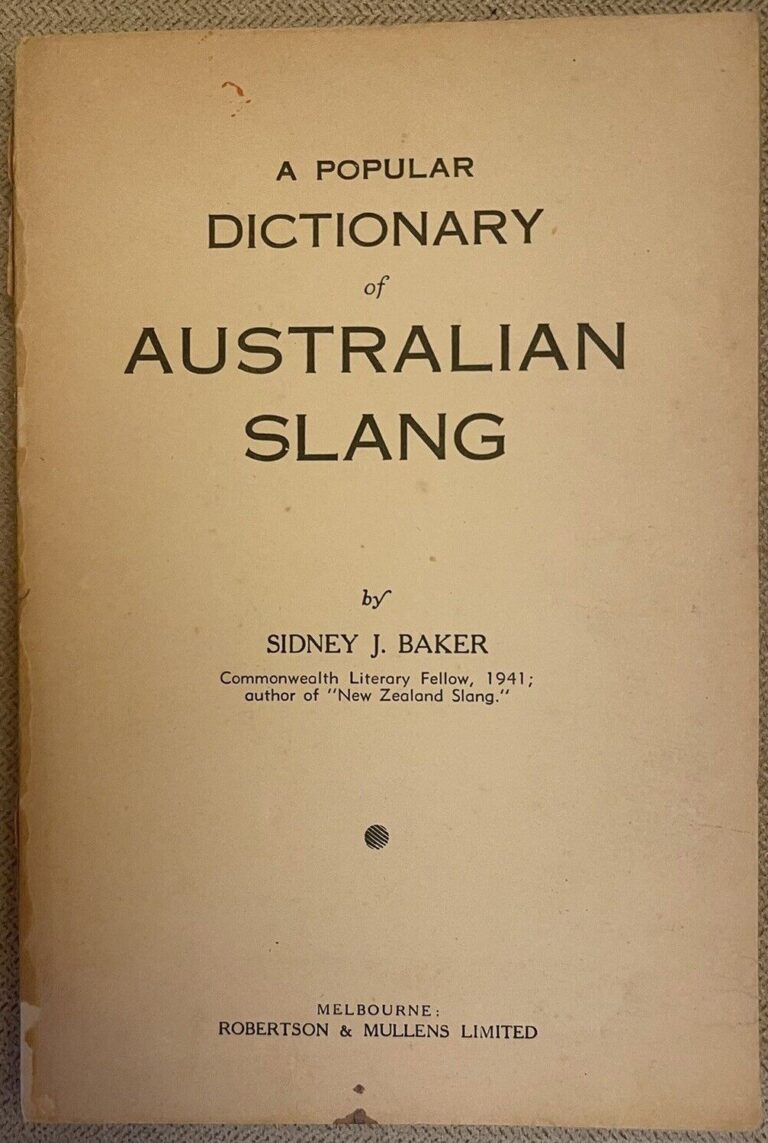

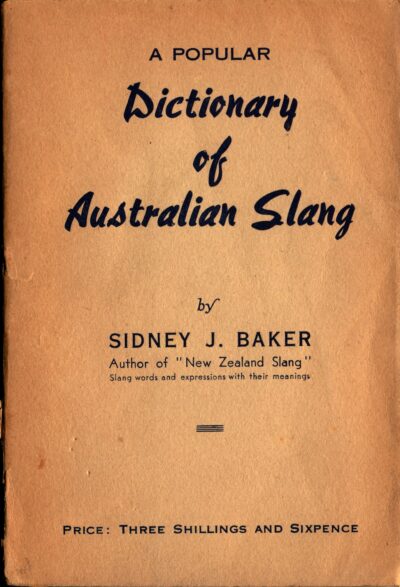

Sidney J. Baker, A Popular Dictionary of Australian Slang (1941)

Sidney John Baker was a pioneering Australasian philologist who dedicated much of his life to documenting antipodean language.

Born in Wellington New Zealand in 1912 as the son of a journalist, his father’s career likely influenced Baker to develop a life-long passion for words. He attended Victoria University College, but did not graduate and instead migrated to Sydney in 1935. Living in Kings Cross, he styled himself as a young intellectual reading Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Nietzsche, and D. H. Lawrence, and ultimately became a journalist himself working for the Daily Telegraph and Bathurst’s National Advocate.

Visiting both England and New Zealand in the late 1930s, Baker published his first book New Zealand Slang and soon afterwards published A Popular Dictionary of Australian Slang with the backing of the Commonwealth Literary Fund. Baker’s combination of familiarity with and (Kiwi-based) separation from the Australian language made him the perfect person to document its nuances, and the book became an instant hit running to three editions by 1943. The book maintained an egalitarian philosophy which insisted that ‘Slang belongs to everyone and is created by all sorts and conditions of men and women’, with its content drawing on liftmen, businessmen, taxi-drivers, journalists, racing touts, the residents of Long Bay gaol, little schoolchildren, barmaids, clerks, farmhands, ship stewards and hundreds of others, hailing from Darwin to Tasmania and from Sydney to Perth. The book contains more than 3000 colloquialisms, from the familiar like ‘arvo’ and ‘metho’ (dodgy spirits) to the long-lost like a ‘flag’ meaning a 1-pound note. The influx of American troops played some role in contributing to the book’s success as GIs tried to get to grips with the local lingo with a view to wooing the local girls (a particularly embarrassing confusion being that in America ‘knocked-up’ then meant tired as opposed to pregnant).

The Popular Dictionary was to be merely the start of a magnificent career devoted to dominion English, as Baker carefully categorised ‘the language of the soil, the bush, the road and the city’ in such works as The Australian Language, Australia Speaks, and The Drum. Considering how rapidly Australians’ use of language has evolved, Baker’s books are now considered invaluable historical documents, preserving numerous interconnected word cultures that might otherwise have been lost. Baker himself loved this constant progress, saying that:

‘The old academic or pseudo-academic fixation that there is a definable something called Good English, which is pure and beautiful and eternal, and that everything else is Bad English— and accordingly trivial, ugly, and ephemeral — has grown out of man’s puny illusion that he can stop evolution in its tracks.’

Menzies had his own notions of what constituted ‘Good English’ but he seems to have had a warm appreciation for Baker’s enterprise, and he personally bought his copy of the Popular Dictionary from Robertson & Mullens Ltd, Booksellers and Stationers, Melbourne in January 1942. This was just a few months after he had lost the prime ministership amidst accusations that he was somewhat aloof from his colleagues, and one might even speculate that Menzies purchased a copy to familiarise himself with the language of the common Australian (Menzies himself was from a humble background, but though he had to win scholarships to attend university, some of its pretentions are said to have rubbed off on him).

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.