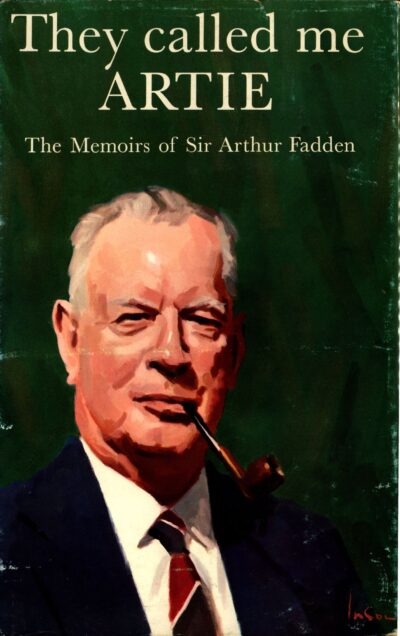

Arthur Fadden, They Called Me Artie: The Memoirs of Sir Arthur Fadden (1969)

Arthur Fadden was a long-standing Leader of the Country Party, who served as Menzies’s Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister from 1940-41 and from 1949-1958 (unofficially, as the latter post was not fully recognised until 1968). Fadden also served as Prime Minister for 40 days after Menzies’s resignation in August 1941, and subsequently (and quite unusually for a CP Leader) served as Leader of the Opposition until after the 1943 election – which saw a disastrous result for the Coalition.

Fadden was born in 1894 (the same year as Menzies) in Ingham, Queensland. The child of Irish immigrant parents, he attended state school until age 15, when he left to work as billy-boy to a gang of cane-cutters. Fadden later became an accountant, which was his primary career until he entered politics; unusually stepping up through each tier of government, as he was elected to Townsville City Council, Queensland State Parliament, and then finally in 1936 Federal Parliament.

They Called Me Artie is Fadden’s political autobiography, and as you would imagine, it contains a number of insights into his lengthy association with Menzies. Fadden recalled that he had been impressed by Menzies from an early stage, and always viewed him as a future Prime Minister. He was therefore quite taken aback when he heard that Earle Page was planning to launch his now infamous attack on Menzies in the aftermath of Joseph Lyons’s passing in 1939; and even as a young backbencher Fadden warned his leader not to go through with it. When these warnings were ignored, Fadden was so disgusted that he led a group of MPs who temporarily disassociated themselves from the Country Party, but he maintains that he nevertheless took ‘no pleasure’ in seeing Page lose the leadership of the party in the subsequent fall-out.

Fadden is far more candid about Page’s replacement Archie Cameron, whose ‘unstable characteristics, unnecessary aggressiveness and dictatorial tendencies’ quickly jeopardised his leadership. As a consequence, in 1940 there was yet another leadership ballot, which saw Page and Jack McEwen repeatedly get an even number of votes, and as a consequence Fadden was called in as a compromise candidate to break the deadlock – biographer Tracey Arklay adds that Fadden was chosen because he was believed to be the best man to negotiate with Menzies and the UAP.

Due to this elevation, Fadden served as Acting Prime Minister during Menzies’s trip to discuss vital war matters in Britain in 1941, during which time Fadden tried desperately to hold a fractious political situation together while also preparing the nation for an increasingly likely conflict with Japan. There was no ill-will about being put in such a difficult situation, with They Called Me Artie insisting that ‘Mr Menzies had loyal followers awaiting him, regardless of anything certain people might say… any success I had achieved as leader during his absence was attributable to the example he had set, to the cooperation received from every member of the Cabinet team and to the understanding and help of John Curtin and his Advisory War Council colleagues.’

The book also fiercely denies that Fadden ever had doubts about Menzies’s leadership, which were rumoured to be a contributory factor in the latter’s resignation, saying that ‘I want to emphasize that while Menzies was abroad, at the time of his return and throughout the remainder of his term, he had the unqualified support and loyalty of myself and the Country Party’. Fadden took no delight in becoming Prime Minister on the back of Menzies’s troubles, particularly as ‘the survival of the government rested on rotten reeds – the two unpredictable Independents’, and he offered Menzies the post of Minister for Defence Coordination in order to make full use of his vast experience. Because of this continuous loyalty, Fadden was quite hurt when in the censure debate which brought down his Ministry:

‘Menzies did not speak though he was still Leader of the United Australia Party, a senior member of the Government and one who was thought to have some influence over [key independent] Coles. In silence he allowed the tide to swirl against my Government.’

Menzies disagreed with the fact that the Country Party Leader continued as head of the Opposition afterwards, and this was a contributory factor to further divisions during the 1943 election when Menzies spoke at Kooyong and ‘To the amazement and chagrin of my colleagues and myself, Menzies vigorously disassociated himself from my advocacy, on behalf of the Joint Opposition of which he was regarded as a member, of post-war credits.’ This ‘stab in the back’ provoked what the book claims was the only time in Fadden’s political life when he publicly criticised Menzies. But in the aftermath of the election reconciliation and hope were forthcoming:

‘By determined effort and persuasion Menzies picked up the unpromising bits and wove them again into a united party fabric, the Liberal Party. In doing so he achieved one of his greatest political triumphs. He even tried to lure the Country Party into participation but, adhering to our traditional principle of separate entity, we declined to attend the conference in October 1944 at which the other groups merged. This was the beginning, though only the beginning, of the road back for Menzies and myself and the non-Socialist parties we led.’

The Coalition parties subsequently led a joint endeavour to oppose the ‘socialist’ designs of the Labor Government, winning office, and leading Fadden to reflect on how Menzies’s evolved and improved between his stints as Prime Minister to become one of the nation’s greatest leaders, albeit remaining a flawed human being:

‘I say, with all respect, that Menzies had attained a maturity in leadership which was lacking during his previous term of office. I always have and always will admire the outstanding attributes with which God endowed him. I had sympathized intensely with him for all that happened on his return from his mission abroad in 1941. He was then the victim of circumstances which arose in his own party though he had given enormous and creditable service to the nation in helping to put Australia on a sound war footing.

I have said that the good Lord endowed him with great attributes, but his natural assets sometimes became liabilities, for he seemed to expect the same degree of intelligence from others with whom he was associated as he possessed himself. I once reminded him that if all the barristers in Selborne Chambers had had legal abilities equal to his own, he probably would not have been leader of the Melbourne Bar. On another occasion I told him that I had been reading Emerson’s essays in which the writer expounded “a law of compensation” to illustrate that Providence did not intend all men to be equal but rather made each to play a separate role. Menzies had been criticizing a Cabinet colleague and I told him that while God had not intended our friend to be a jockey (because of his weight) he was certainly cut out to be what he was — namely one of our best vote-catchers. Menzies said my little homily had done him good, but I’m not sure.

His own educational attainments and the way he applied them made me conscious of my lack of similar educational qualifications, more especially as he so keenly respected a university background. Nevertheless the fact that I had been trained on the less important campus of “Walkerston University” and had rubbed shoulders closely with my fellow human beings in the field of sport and in business, was probably a contributing factor to our lasting and effective partnership. I sometimes reflected, however, that had I been the baker supplying the bread to a university, my standing with him might have been higher.

It was probably unfortunate for Menzies that success had come to him so quickly and with such apparent ease. I am certain that his first taste of political defeat acted like a tonic, for it was a novel and instructive experience which made him a better leader afterwards.

Like so many others I both enjoyed and appreciated his oratory because, in addition to a superb vocabulary, he was a first-class actor. But there were some words which he could not easily or graciously include in his repertoire – words of congratulation, appreciation, gratitude, mateship, or warm-hearted encouragement; he had a tendency to take his loyal friends for granted and impose on their loyalty.

His speeches sometimes gave the impression that he did not care if he walked over dead bodies and created the feeling that he was talking down to people less perfect than himself. But despite this he won the applause and the political reactions we sought – in particular the precious votes to keep us in office and ensure that our policies could be carried out. He not only won but kept on winning.

At all events, when the history of national and international statesmen is faithfully recorded, it must be proclaimed that Sir Robert Gordon Menzies bequeathed a legacy of distinguished public service which brought honour to himself and permanent benefit to the land of his birth.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.