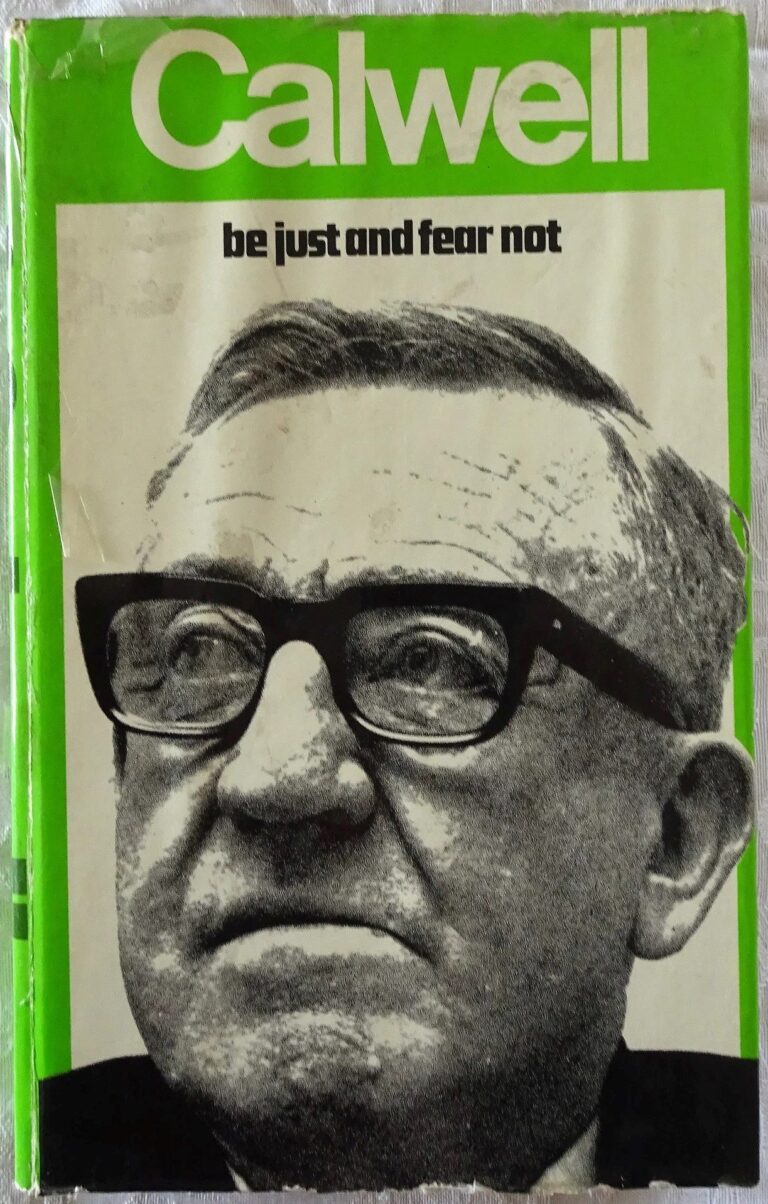

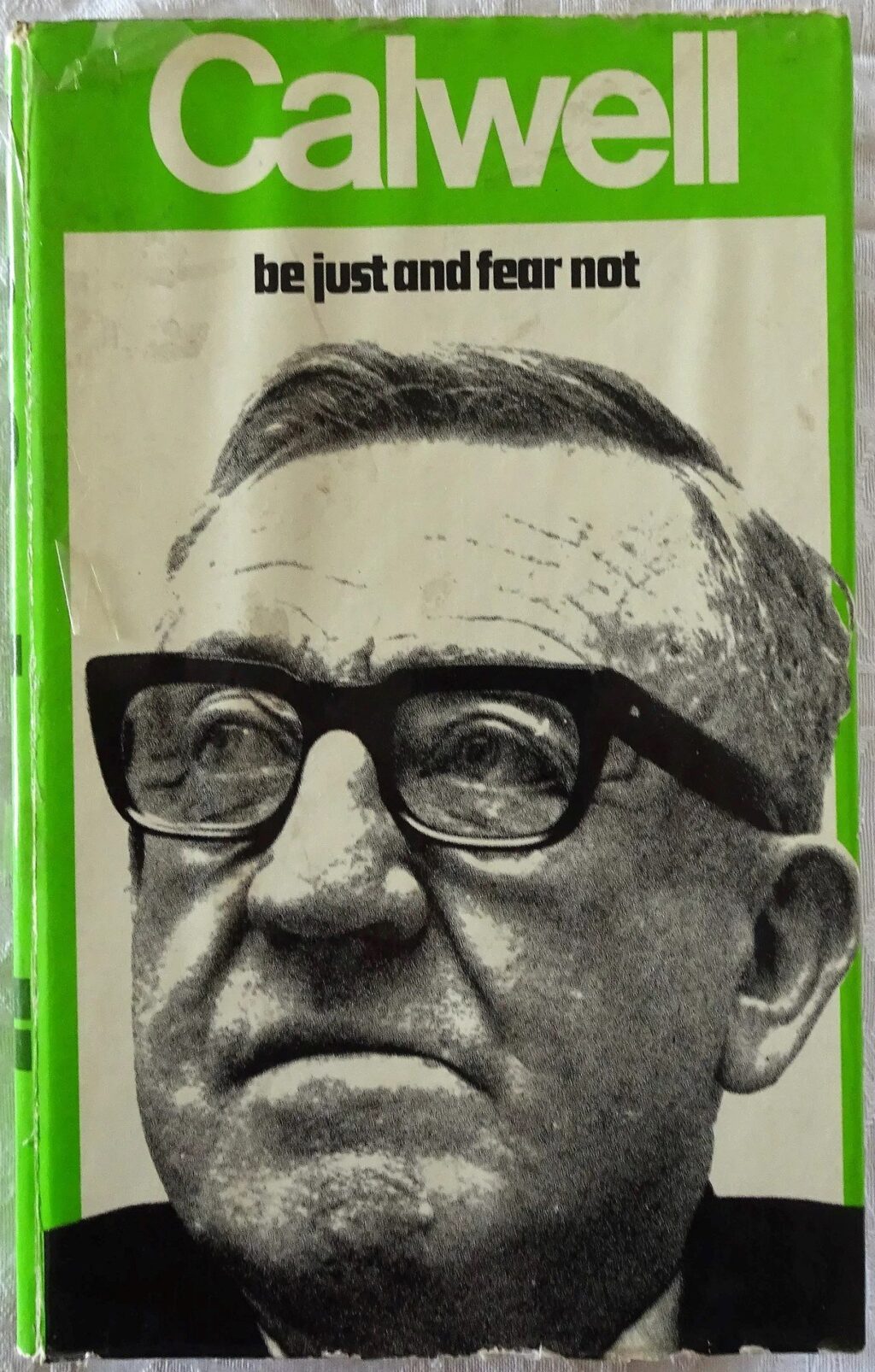

Arthur Calwell, Be Just and Fear Not (1972)

Arthur Augustus Calwell was the Leader of the Australian Labor Party and Federal Opposition from 1960 until 1967. He faced off against Robert Menzies in two Federal elections, narrowly losing the 1961 poll in one of the tightest results in Australian political history.

Calwell was born in West Melbourne in 1896, the son of a police constable and the eldest of seven children. Raised as a Catholic, he attended Christian Brothers’ College in North Melbourne before joining the Victorian public service. When the First World War broke out Calwell tried to enlist in the AIF but was rejected on the grounds of his age. However, as the conflict dragged on he would grow to be more critical of Australia’s involvement, and he fought hard for the ‘No’ campaign during the conscription referendums.

Part of the reason for this shift in perspective was Calwell’s involvement in the Australian Labor Party, which he joined at the tender age of 19, while he also became heavily involved in public service unions like the State Service Clerical Association and the Australian Public Service Association. An important ALP backroom figure by the 1930s, Calwell worked on the election campaigns of the Federal Member for Melbourne William Maloney and also collaborated with John Curtin in fighting for ALP unity and combating the divisive influence of Jack Lang.

He was rewarded for his efforts when he was preselected as Maloney’s replacement in the lead up to the 1940 election (the first poll Menzies ever faced as Prime Minister). In Parliament Calwell clashed with John Curtin for failing to implement Labor’s social program during the wartime budgets of 1941 and 1942, and also for narrowly extending the area in which Australia’s conscript Militia could be forced to serve (in strong contrast to Menzies, who set up a splinter group in the UAP called the National Service Group to push the opposite perspective on the same issue).

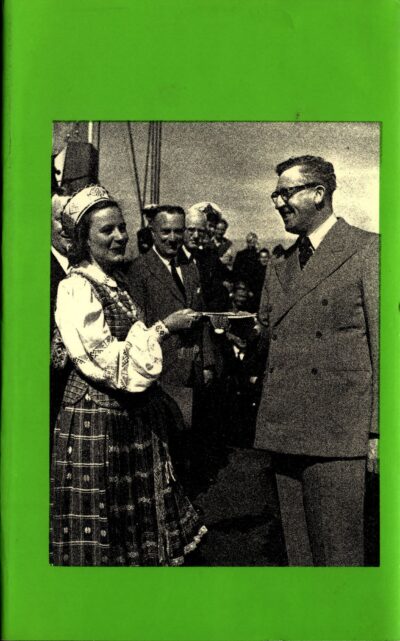

Despite this criticism, after the 1943 election Calwell was made Minister for Information, responsible for the tricky issue of wartime censorship, and began his climb up the hierarchical ladder of the parliamentary ALP. When Ben Chifley became Prime Minister in 1945 he elevated Calwell to be Minister for Immigration, and it was in this role that Calwell made his most significant achievement in overseeing the first stages of Australia’s post-war immigration boom.

Calwell was also responsible for the scheme to greatly increase the size of Parliament and introduce proportional representation for the Senate in the lead-up to the 1949 election. This succeeded in entrenching Labor’s Senate representation such that Menzies would be forced into a double dissolution in 1951, but the new House of Representatives seats also helped to entrench the Coalition’s electoral majority for the long term.

Despite his Catholic faith, Calwell was an early critic of ‘The Movement’ which tried to combat communist influence within the Australian union movement. This made it almost inevitable that he would side with Evatt during the Great Labor Split, which was most devastating in his home State of Victoria. When Evatt finally retired after doing much damage to his party, Calwell was elected as his replacement and did an admirable job in trying to clean up the political mess he was left with.

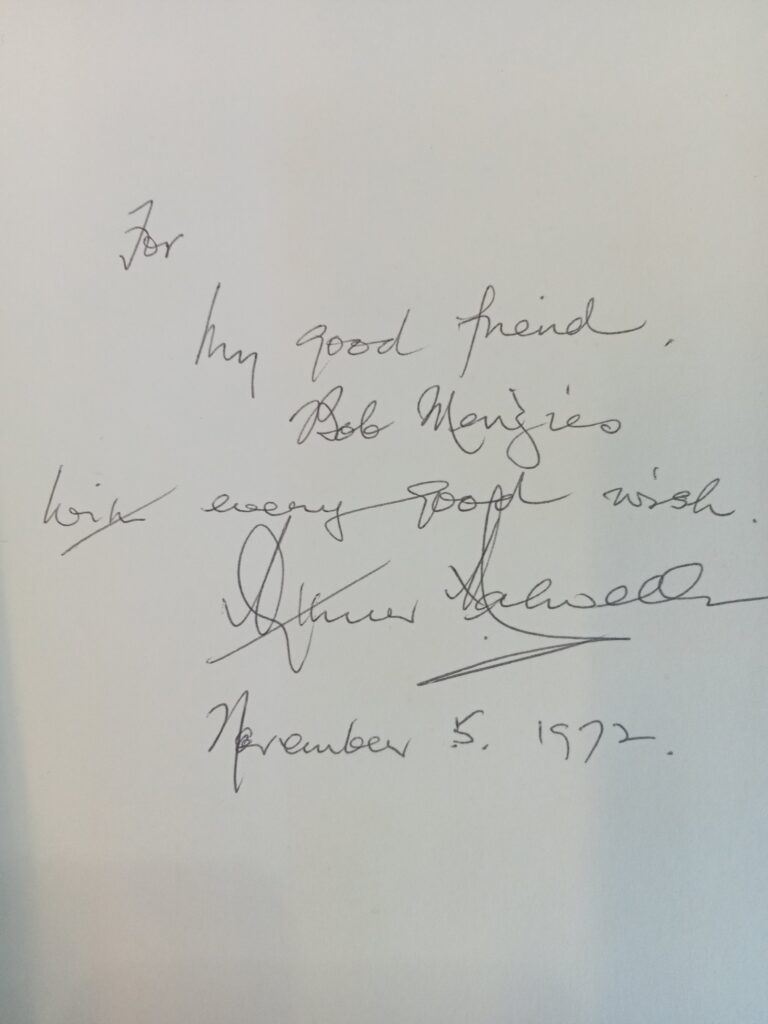

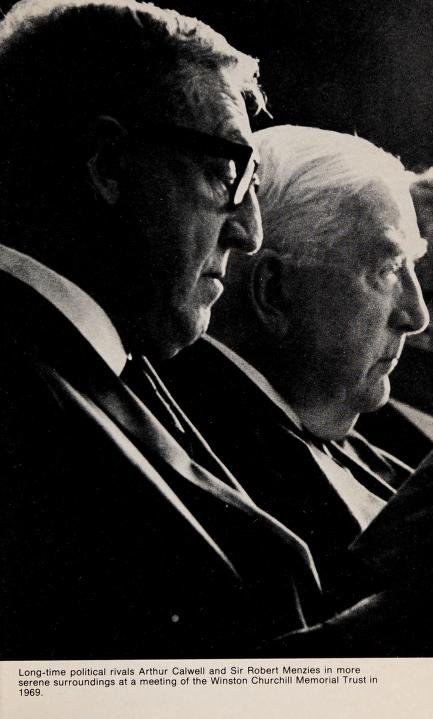

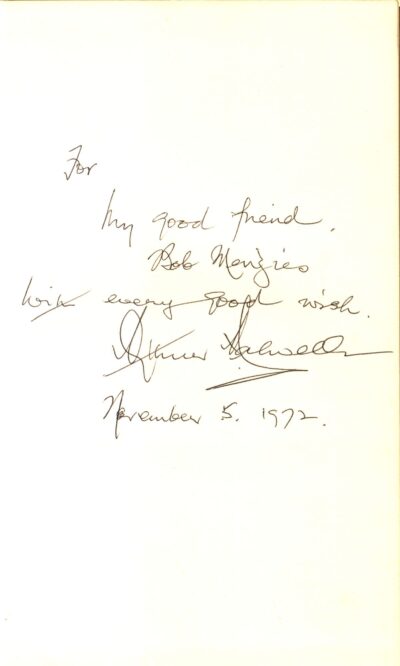

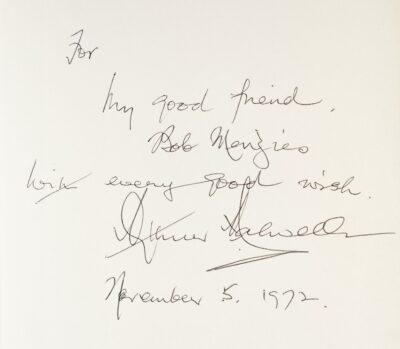

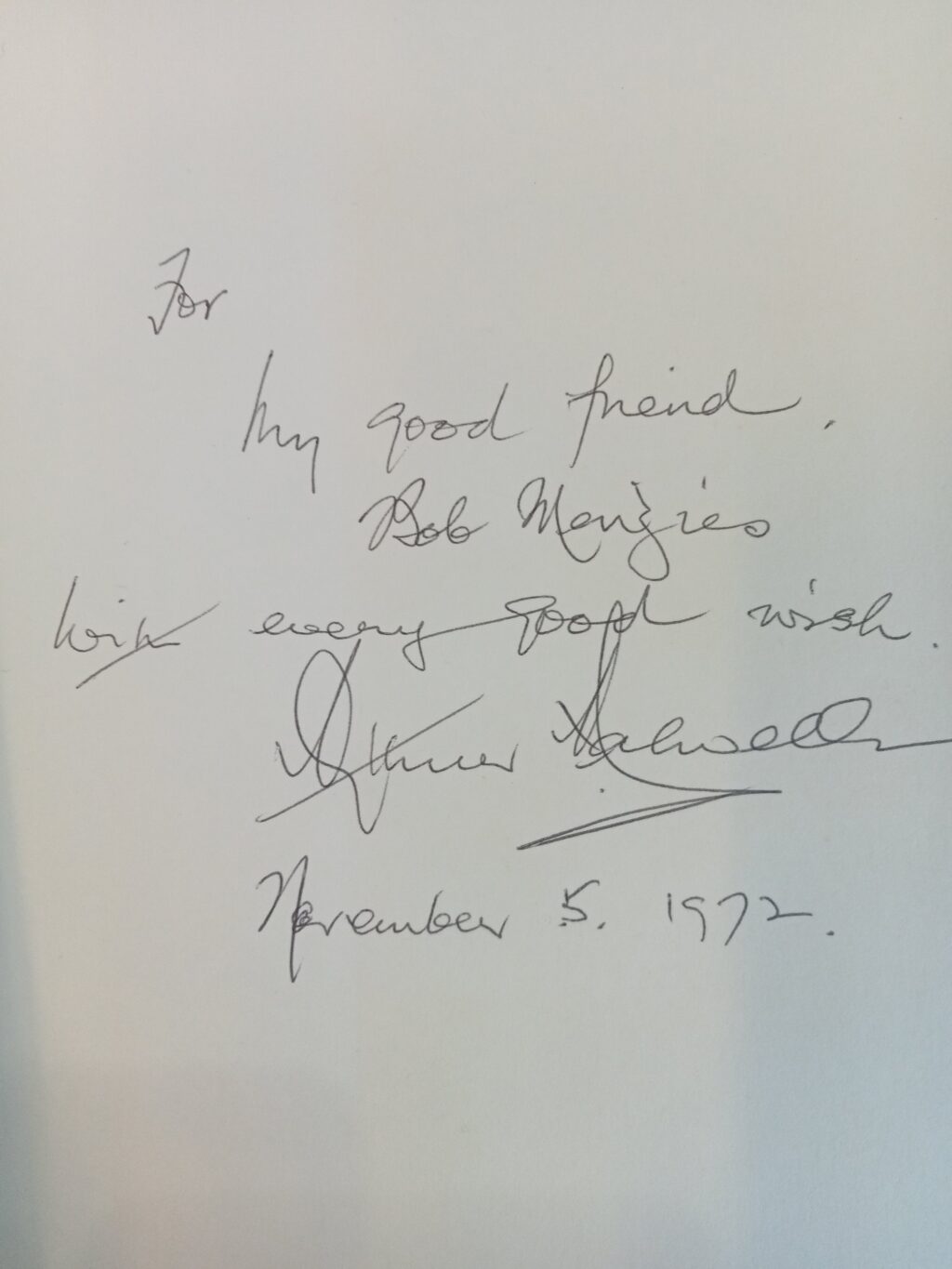

Menzies had great respect for his political opponents, and was personal friends with the three Labor C’s (Curtin, Chifley and Calwell). As Chancellor of the University of Melbourne Menzies nominated Calwell for an Honorary Doctorate, and when Calwell died in 1973 Menzies is recorded as sayinhg that ‘In private life we have been good and close friends and I will miss him very much’. Menzies’s copy of Be Just and Fear Not, Calwell’s autobiography, provides evidence that this sentiment was a two-way street. It is inscribed ‘For My good friend Bob Menzies, With every good wish. Arthur Calwell, November 5 1972.’

The book is a revealing artefact in other ways, most notably for the insights it provides on Calwell’s opinion on Menzies and various aspects of Australian political history in which he was involved. Calwell devotes an entire chapter to Menzies, who he described as having ‘a great capacity for being magnanimous’, though notably he is most interested in talking about Menzies’s wartime leadership rather than his subsequent record stint as Prime Minister.

Calwell was utterly convinced that Menzies should have never resigned from the prime ministership in 1941, ‘that he allowed himself to be bluffed into abdicating the highest and most important elective office in the land’. According to Calwell, Menzies knew that the Japanese were about to enter the war and only had to hold out for a couple more months until they did, for once that had happened his political position would have been unassailable. Calwell also notes that Arthur Coles, one of the independents who helped to bring down the short-lived Fadden Government, would never have voted with Labor in the House had Menzies still been leader.

It is a fascinating historical ‘what if’, made all the more intriguing because it is provided by an important contemporary political player.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.