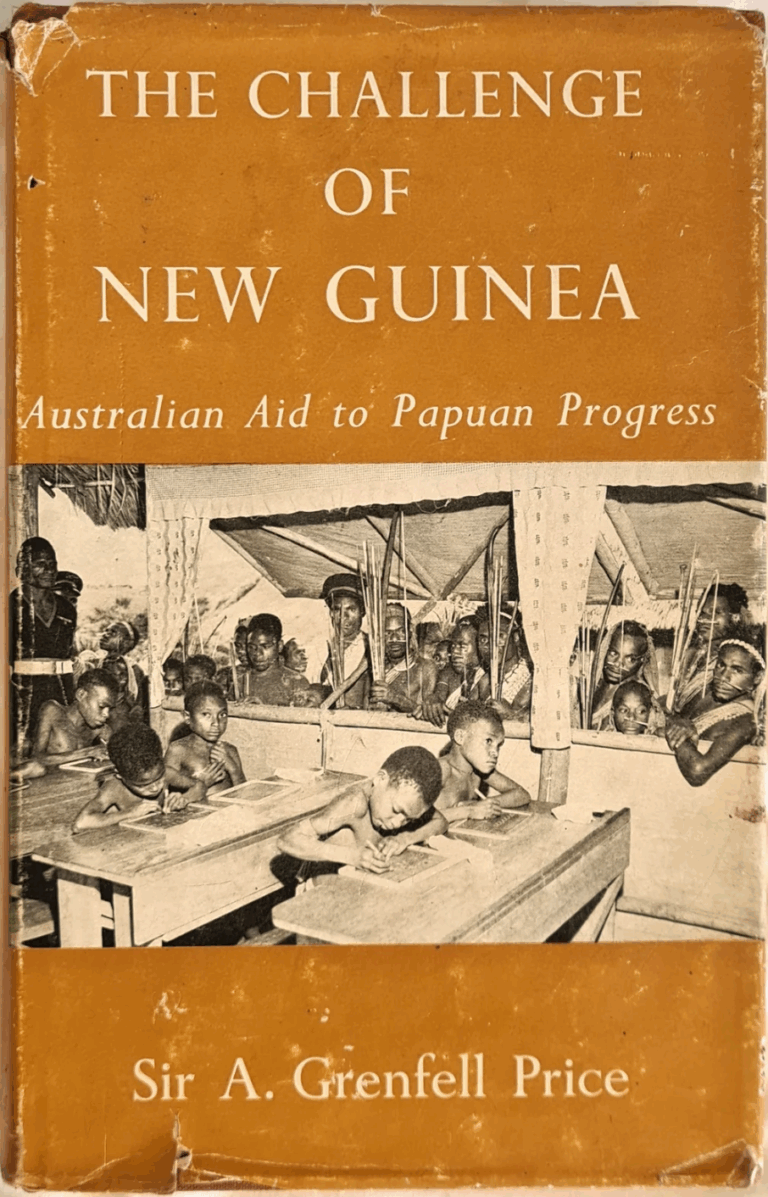

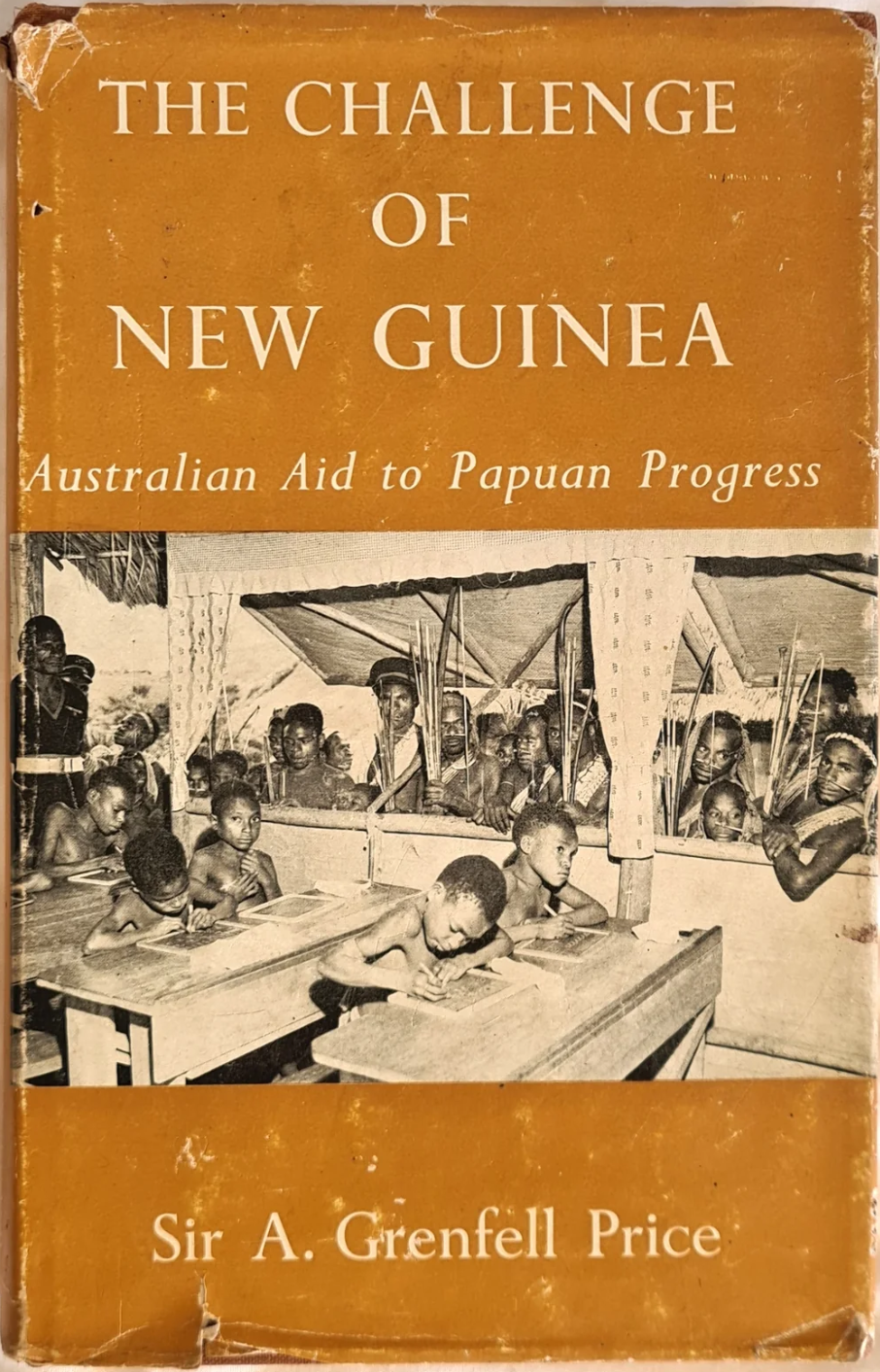

Sir Archibald Grenfell Price, The Challenge of New Guinea: Australian Aid to Papuan Progress (1965)

Australia’s administration of its territories of Papua and New Guinea was the subject of intense international scrutiny during the Menzies era. This was after all the age of decolonisation, yet here was Australia holding on to a colonial possession until as late as 1975. Not for the purposes of economic exploitation – for indeed PNG was a major drain on the Australian federal budget, as it has remained post-independence. But out of a mix of strategic security reasons – the territory was seen as providing a vital buffer zone in which an enemy could be repelled before they got to Australia, as had proven the case with Japan during World War II. And a genuine sense of altruism which held that the administration of PNG came with a profound obligation to develop her democratic institutions and economy, such that when the day came for her independence, PNG locals could be set up for future success.

That being said, the Menzies Government and its responsible Minister for the Territories Paul Hasluck were also acutely aware of the immense obstacles that needed to be overcome before such success could be assured. This led to a great deal of defensiveness about what Australia was doing in PNG, and the slow path that was being taken towards independence. Such defensiveness is clearly evident in The Challenge of New Guinea, which describes the Australian administration of the territory as an act of ‘philanthropic colonialism’. The book’s author, Archibald Grenfell Price, was undoubtedly well-qualified in his knowledge of Pacific history and the colonial experience from a litany of publications produced while working at the University of Adelaide. But he was equally something of a Menzies partisan who had served a brief stint in the House of Representatives, been involved in the founding of the Liberal Party in South Australia, and more recent to the book’s publication, played a central role in the government’s creation of the National Library of Australia.

Exhibiting the positive bias one might expect given these connections, The Challenge of New Guinea critiques the ‘over-centralisation’ of some of Hasluck’s policies, but otherwise endorsed their validity and stressed the need for patience amidst the growing international rancour:

‘The world should recognise that the recent Australian development of the Territory has been so spectacular and philanthropic that the United Nations should seek to remedy the really grave harm they have done and trust the Australian-New Guinea partnership to proceed as both parties wish on the present co-operative lines. This will enable them to decide together the date for New Guinea independence, or, if the partners prefer, the admission of the territory to the Australian Commonwealth as a seventh state, snuggling its copra, cocoa, coffee, tea, timber and other tropical products into the Australian economy’

In its ‘highly moralistic tone’, Price’s book echoed the line of reasoning Menzies had himself put before the UN General Assembly in October 1960, when Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev attacked Australia as an alleged unrepentant colonial despot:

‘in the course of this Assembly Mr. Khrushchev was good enough to make some references to my own country as a member of a group of countries and to our position in relation to the territories of Papua and New Guinea. He calls upon us to give immediate independence and self-government to these territories. As a piece of rhetoric, this no doubt has its points·– we can all admire rhetoric; we hear a good deal of it. But it exhibits a disturbing want of knowledge of these territories and of the present stage of their development. Nobody who knows anything about these territories and their indigenous people can doubt for a moment that for us in Australia to abandon our responsibilities forthwith would be an almost criminal act.

Here is a country which not so long ago was to a real extent in a state of savagery. It passed through the most gruesome experiences during the last war. It came out of that war without organized administration and, in a sense, without hope. It is not a nation in the accepted term. Its people have no real structure of association except through our administration. Its groups are isolated among mountains, forests, rivers and swamps. It is estimated that there are more than 200 different languages — not dialects, but languages. The work to be done to create and foster a sense and organism of community is therefore enormous. But, with a high sense of responsibility, Australia has attacked its human task in this unique area.

Since the war, some form of civilized order has been established over many thousands of square miles which were previously unexplored. We have built up an extensive administration service from nothing to a total of thousands of public servants, local members of the public service and administration indigenous employees. We have created five main ports with modern equipment. We have built 5,000 miles of road, over ICO airfields. We have established and improved postal and telecommunications services. We have built 4 large base hospitals, ICO subsidiary hospitals, 12,000 aid posts and medical centres, 778 infants and welfare clinics. We have trained hundreds of doctors and nurses, thousands of native medical assistants. We have established 4,000 schools, which are attended by 200,000 pupils. We have established large stock stations and a great forestry industry.

I could go on almost indefinitely. All this has been done in a few years since the war. The achievement has not been without cost. We are a very strange colonial Power, if I understand the sense in which that term is used. We have put many, many more millions into Papua and New Guinea than have ever come out, or ever will come out. Like the Netherlands, whose representative spoke last night about its side of New Guinea, we regard ourselves as having a duty to produce as soon as it is practicable an opportunity for complete self-determination for the people of Papua and New Guinea. We have established many local government councils in order to provide training in administration. We have set up a legislative council on which only the other day we substantially increased the number of indigenous representatives.

And yet Mr. Khrushchev includes us in his diatribe against “foreign administrators who despise and loot the local population”’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.