David Daiches, Robert Burns and His World (1971)

One of the most revealing records in Australian political history is the fact that since the electoral defeat of the Scullin Government in December 1931, no party elected to government has failed to win a second term. This speaks to the Australian electorate’s innate preference for stability and continuity, as also evidenced in its propensity to vote down unnecessary constitutional change. It also demonstrates that our supposedly ‘short’ election cycle is not the handicap that many make out, as most administrations can have at least six years in office, unless they do something catastrophic.

Scullin’s overseeing of the Great Depression, and the manner in which that split his Labor Party to both the left and right, stands out as a clear example of the kind of disaster that would have to befall a government for it to be thrown out in haste. Although it should equally be noted that his opponent Joseph Lyons ran a uniquely successful campaign, building momentum from the All for Australia Leagues and an innovative public relations effort, to propel him to widespread popularity. And also that since he had never been a Nationalist, Lyons carried with him none of the baggage of the Bruce Government that had been defeated two years before, as the Australian people do not easily forget why they have recently ousted a party from office. Amounting to a perfect formula for forcing a one-term government.

In the 94 years that have since passed, the upholding of this record has left a lot of disappointed Oppositions in its wake. Particularly so in recent years, where the 1998, 2010 and 2016 elections all stand out as some of the most closely run in all of Australian political history. But while the defeated Opposition Leaders in these instances could at least console themselves with the fact that they were up against history, no such consolation was available to Robert Menzies and his newly-founded Liberal Party when they were defeated in 1946.

Indeed, because so many of the Liberals’ leading figures had been involved in the success of Lyons in 1931, their hopes for victory were remarkably high despite the UAP’s crushing defeat in 1943. In a ‘Forgotten People’ radio broadcast made shortly after he had been elected Leader of the Opposition, Menzies drew attention to what was then still recent memory:

‘In the last few days my mind has run back very much to the recollection of what happened in 1930 and 1931. At the end of 1929 Mr. Scullin had secured a record majority in the House of Representative. Gloomy prophets said that Labor was in for ten years; that all was over. Yet, Mr. Latham, as he then was, becoming Leader of not more than thirteen Party Members who included such doughty Parliamentary fighters as the late Henry Gullet, Archdale Parkhill, and the late Charles Hawker, to say nothing of others who are still in the Party, so organised and conducted an Opposition that it became first a debating force and then a National force. The Government disintegrated and in 1931 was swept away at a general election. For the efficacy of the Opposition, numbers are of small importance. “It’s dogged that does it”. I have been long enough in Parliament never to under-estimate a political opponent or a political problem. But I want all of you to know that on this job, the Opposition’s tail is up!’

However ‘up’ their tail might have been, the Coalition would pick up just six seats in 1946, far below what was needed to challenge the government. But even if the general swing fell well short of expectations, there were some electorates which bucked the trend, highlighting the eternal imperative of quality candidate selection and local campaigning.

One of the most notable was the Tasmanian seat of Franklin, where a 25-year-old Liberal candidate named Bill Falkinder achieved the 10% swing required to become the local member. A feat made all the more impressive by the fact that in the neighbouring seat of Wilmot there was a swing towards the government which saw sitting Liberal MP Alan Guy lose his place in the House of Representatives.

Born in 1921 as the eldest of five children, Falkinder had attended Hobart High School before the death of his father forced him to leave without matriculating, in order to help financially support his younger siblings. Soon after the war broke out in 1939, he had left his job as the clerk of an electrical goods store to enlist in the Empire Air Training Scheme. Flying in numerous sorties over Europe, surviving a plane crashed that killed four other crewmen, and ultimately being promoted to flight lieutenant.

Boasting this decorated service record and a humble backstory, Falkinder was able to win over many of the working-class voters in his electorate, and was given an early promotion by Menzies in February 1950, when he was appointed assistant to the minister for commerce and trade. The following year, the Liberal Leader even named the young and sporting MP to play in the inaugural Prime Minister’s XI match. But their relationship soon soured as Falkinder maintained a fierce ‘spirit of independence’ such that he was often prone to criticise government policy. Forcing Menzies to return him to the backbench in May 1952, where Falkinder remained until his retirement in 1966.

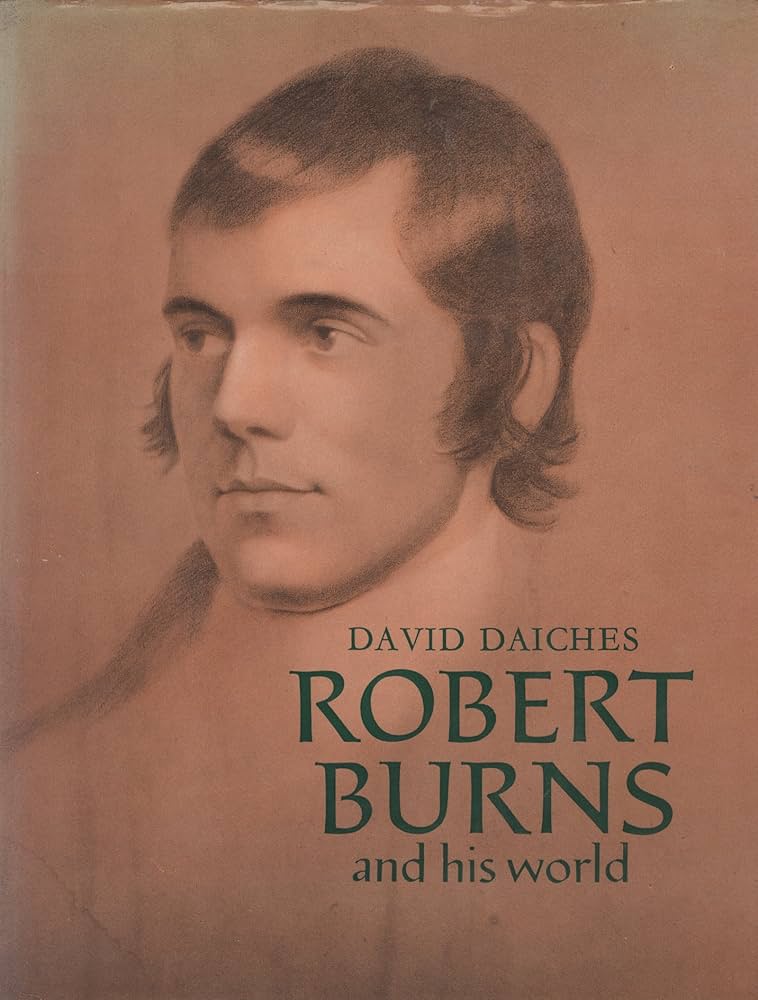

Despite never really living up to his potential and repeatedly being bypassed for promotion, Falkinder held no lasting bitterness towards the prime minister. And would even go out of his way to visit Menzies in his retirement, when many others neglected to do so. It was presumably on one such visit that Falkinder gave Menzies his copy of Robert Burns and His World, a thoughtful gift for a proud Scotsman that is sure to have been appreciated.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.