Max Dupain, Georgian Architecture in Australia (1963)

Robert Menzies was a strong advocate for women pursuing a tertiary education, at a time when female university attendance was not yet common. In his Forgotten People Broadcast on ‘Schools and the War’ he boldly proclaimed:

‘Higher education for women must come to be regarded as normal and not as the eccentricity of a potential “blue stocking”. For the blunt truth is that the equality of the sexes cannot be maintained if a slapdash training in a few minor ornamental accomplishments is considered an adequate education for the daughter of the house’

It was thus a very gratifying occasion for Menzies when on 11 April 1964, he was able to open St Hilda’s College at the University of Melbourne. While the University had opened a women’s college in 1936, St Hilda’s was the first women’s college dedicated to female adherents of the Presbyterian and Methodist Churches, whose men had long been accommodated by Ormond and Queen’s Colleges respectively. Menzies himself had been brought up in both Churches, and ended up attending Ormond even though many of his Wesley College schoolmates went to Queen’s. When the latter had been opened by Revd Edward Sugden in 1888, he had openly stated that ‘I hope we soon have a hostel for women in these grounds’, an opinion that back then would have been even more distinct than in Menzies’s day.

St Hilda’s College was thus the belated fulfillment of a 75-year-old promise. But it was also one in which Menzies had taken a very personal role. As he related in the speech he gave at the opening:

‘[W]hen I had first appointed a committee to look into the financial position of the University, a somewhat morbid task at the time, I was told by one of those concerned that the committee was ill-disposed to recommend any payment in relation to a residential college on the remarkable ground that a residential college was a luxury, and if people wanted it they could pay for it. But there was no reason why it should be associated with any funds passing from the Government to the University. And with that quiet, diplomatic manner for which I believe I am celebrated, I said to them, no recommendation for the residential colleges then the whole recommendation is out… [O]ne of the great things that has come to be realised over the centuries is that students learn from each other and that they are going to live in a human world full of human problems, full of the difficulties of human relationships and that the sooner they start to realise that there are other people and get to know what they are like and how they think the better.’

He went on to restate his long-standing belief that women belong at the University, and record the stubborn opposition which had to be overcome in founding a new women’s college:

‘I remember when someone was bold enough to suggest that there ought to be a women’s college over on that triangular piece of land – along there – a couple of ardent opponents went and pegged out a mining licence on the site… so that they might prevent this devastating waste of public money in the education of women… I think all over the world it has been realised that a country does itself infinite service when it provides the highest educational facilities and all other facilities of research and whatever they may be, for people of both sexes’.

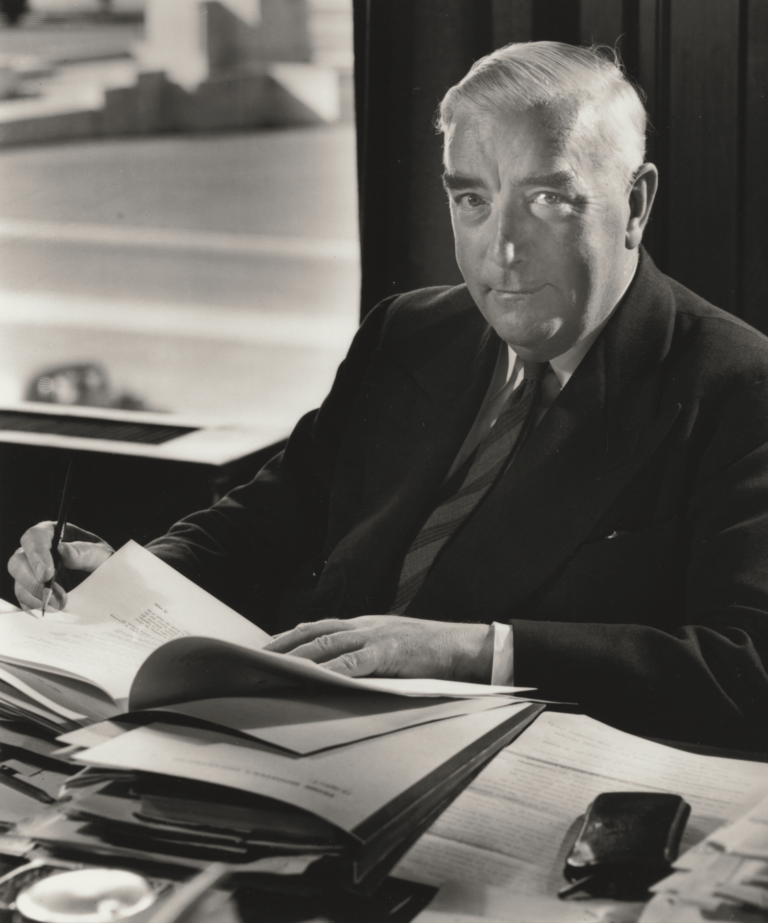

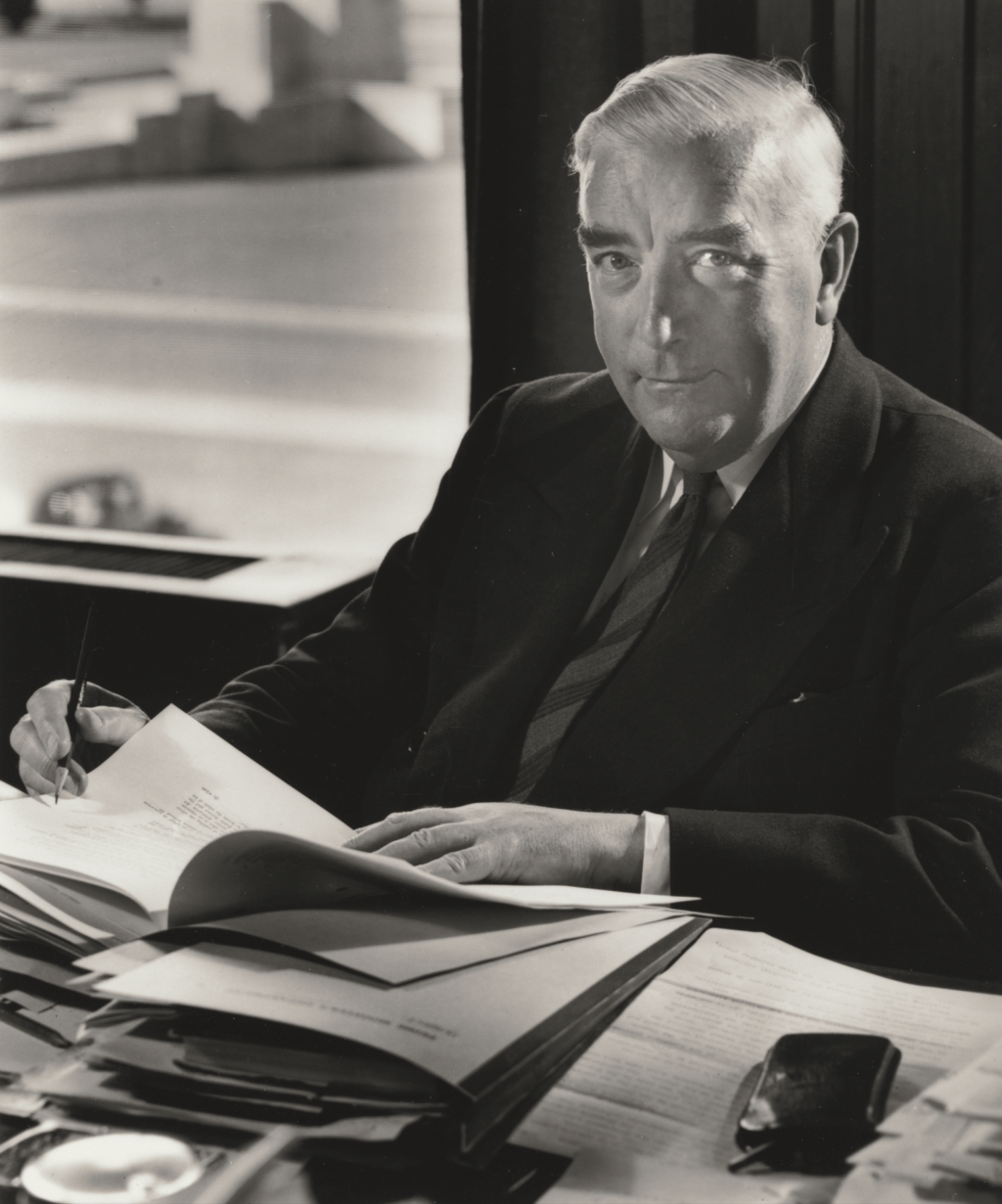

As a memento of the opening, Menzies was gifted a copy of Georgian Architecture in Australia, and he must have been too polite to tell them that he had been given the exact same book by a friend the preceding August. The book itself is a collection images taken by legendary Australian photographer Max Dupain – whom Menzies would have known quite well. After all, Menzies had said for Dupain to take his portrait for a famous London newspaper in 1950.

When Dupain asked Menzies to pretend to read, his private secretary was aghast at such unnecessary time wasting, saying:

‘Don’t ask him to pretend to be reading. Here – give him this copy of the Public Service Bill and let him keep on working’.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.