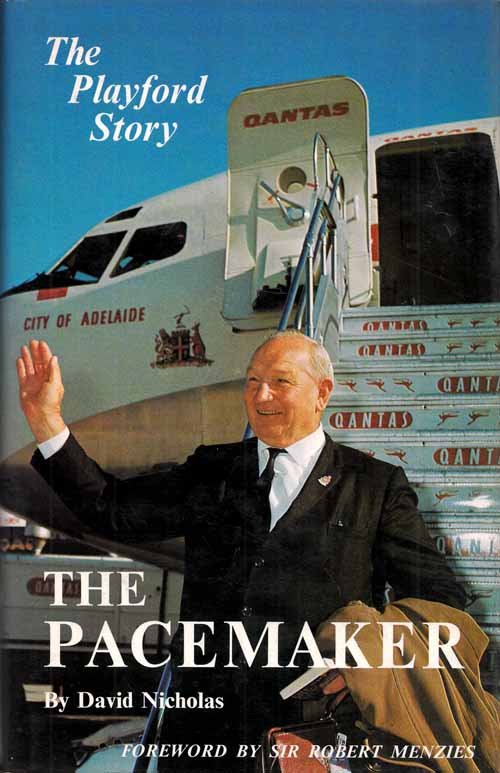

David Nicholas, The Pacemaker: The Playford Story (1969)

While Robert Menzies was Australia’s longest serving prime minister, he was not Australia’s longest serving political leader. That distinction belongs to Sir Thomas Playford IV, who served as Premier of South Australia from November 1938 until March 1965. His career thus overlapped with all but 10 months of Menzies’s stint as PM, and although both men were Liberals, Playford never shied away from firmly impressing the needs of his state on his federal counterpart – such that Menzies openly admitted to finding Playford exhausting.

Born in 1896 as the grandson of a South Australian Premier (also named Thomas Playford), Playford was in many respects born for politics. Apart from his notable pedigree, he developed an impressive resume managing the family farm from the age of 13, serving at Gallipoli, and being injured during the Battle of Pozières on the Western Front.

On returning from the War to fruit farming, Playford joined the Liberal Federation – South Australia’s Liberal Party which had evolved out of the 1909 fusion of the Farmers and Producers Union (made up of pastoralists), the Liberal and Democratic Union (made up of small wheat farmers), and the Australian National League (which was more urban/Adelaide based). Building on this uniquely South Australian mix of liberalism and agrarianism, in 1932 the Liberal Federation would merge with the State’s Country Party to form the Liberal and Country League. This would prove to be an enduring political entity, making up the only united and successful Liberal Party to attend Menzies’s 1944 Unity conferences, when the rest of the nation’s centre-right organisations were a divided and scattered mess.

As a Liberal farmer who was personally friends with South Australian Country Party Leader Archie Cameron, this arrangement suited Playford perfectly, and in 1933 Cameron persuaded him to stand for a seat in the House of Assembly. From this point, Playford conducted a remarkable rise up the parliamentary ranks, such that when in 1938 Premier Richard Butler resigned to contest a federal seat, Playford was able to succeed him.

Playford’s long reign was due in part to his political pragmatism, and his acceptance of a large degree of state involvement in the economy which left the Labor Opposition with little room to differentiate itself. But it was more due to the infamous ‘Playmander’, the strong pro-country bias in the weighting of South Australia’s electorates. This was something that Playford inherited rather than made, but such was his skill in exploiting the unbalanced electoral system that it became synonymous with his name.

The moral and democratic implications of this gerrymander are not dwelt on in any great length in The Pacemaker, for its author was an unashamed Playford admirer. But the book is nevertheless important in having a foreword written by Menzies which offers some insights into the relationship between two of Australia’s most durable political leaders:

‘Sir Thomas Playford was a great Premier of South Australia; as I believe the greatest in the entire history of that State. Indeed, if a Premier is to be measured by what he did for his own community persistently, constructively, successfully, then I would offer the opinion that he was the greatest State Premier in the history of Australia. I say this in spite of the fact to which I will refer later that, from my point of view, he was a most persistent and exasperating negotiator. Time after time at Canberra during a Premiers’ Conference or Loan Council Meeting, I have gone back to my study after a long and tiring day thinking grim thoughts about Tom. But, inevitably, before I went to bed my judgement had come right and I would find myself saying to myself “Well, after all, he never fights for Tom Playford. He has no personal end to serve. Everything that he does, however much he excoriates my mind, is all done for South Australia”. Having reached this sensible conclusion, I would go to bed and hope to be fresh for the encounter the next morning.

When he became Premier of South Australia so many, many years ago, that State had an unbalanced economy which rested mainly on the rural industries. It was, therefore, a claimant State depending on Commonwealth grants from year to year. Tom Playford saw clearly that secondary industry must be established and developed if South Australia were to become economically broadly based.

During my first relatively brief term as Prime Minister I was able, because I sympathised with his ambitions for South Australia, to lend a hand in such matters as the water supply to Whyalla and the establishment of Munitions Factories in South Australia, to do something to help. He has himself handsomely acknowledged this. But to him, a small beginning was merely a beginning. And so, he pressed on bringing industry after industry to the State so successfully that before he ended his long term he probably had a larger percentage of natural Labour voters than any other State in Australia. Viewed from this point of view, his persistent efforts were calculated some day to defeat him politically. He always struck me as not caring very much about this provided that South Australia became stronger. In this sense he was an altruist and, even in my exhausted moments, excited my admiration.

He was, of course, physically an enormously strong man. As all the arguments went on and we weaker mortals became tired, he seemed to gather strength as he went. Nothing could weary him. Nothing could divert him from the pursuit of what to him and to South Australia and in reality, to all of us, was a great adventure.

I can give a small example of what I mean. I hope that Tom will take no exception to it. After I had gone to West Australia on some political errand and had had a large and possibly noisy meeting in Perth, I would then proceed to the airport to catch a plane to the East. It would be near enough to midnight when we left Perth. In those days it meant arriving at Adelaide at about 6.30 in the morning. After two or three hours of broken slumber on the plane we would arrive at Adelaide. I would look out of the window and, sure enough, there was Tom Playford waiting for me. I used to groan, but there was no escape. He was the only man I ever knew who, at that unnatural hour in the morning, would take me on side and begin to pump propaganda into me hoping, I sometimes thought, to get me in my weakened state to agree to something that he wanted. Time meant nothing to him; South Australia meant everything…

I am glad and relieved that I shall never have to argue with him again, but I want him to know that after all our arguments of the past I remain his most faithful and respectful admirer and friend.’

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.