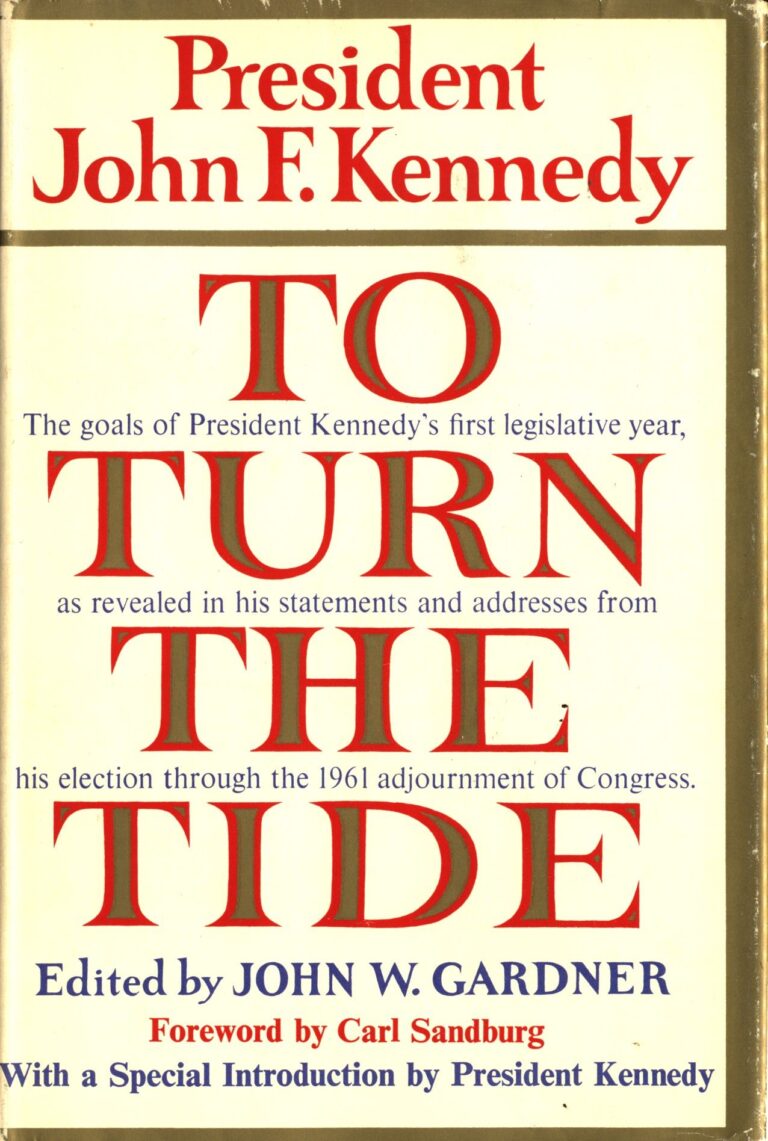

John F. Kennedy, To Turn the Tide: A Selection of Public Statements (1962)

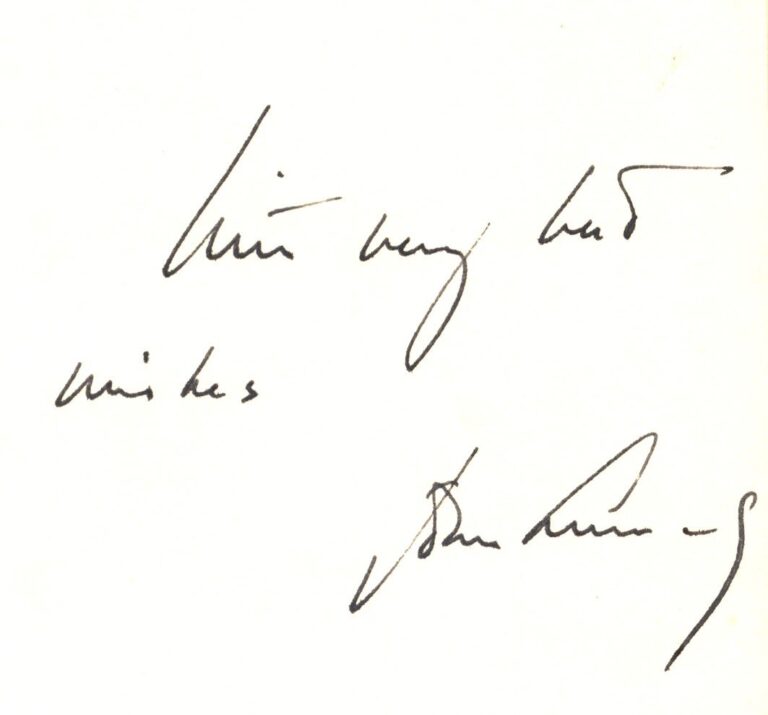

It is a sign of Menzies’s incredible political endurance that as Australia’s Prime Minister he would have personal dealings with five serving US Presidents. John F. Kennedy was the fourth of these, and as America’s youngest ever and first Catholic President, he stood out as a significant contrast to his predecessors. Menzies’s signed copy of To Turn the Tide, which Kennedy sent him in January 1962, is a memento of their relationship.

Menzies first met Kennedy in February 1961, shortly after his inauguration. Menzies was making his annual trip to Britain, and made a point of stopping over in Washington along the way to meet the new leader of the Western World. Despite Menzies having been close to Vice President Nixon – the man whom Kennedy had narrowly bested in a close-run election, the two leaders got on well, with Kennedy reminiscing about his time serving in the Navy in the Pacific theatre. In particular, he related the story of how Australian serviceman Reg Evans had helped to daringly rescue Kennedy and his crew when their torpedo boat had been wrecked off the coast of the Soloman Islands in 1943.

Menzies visited Kennedy again in June 1962, receiving full military honours on arrival before flying in Kennedy’s personal jet from New York to Washington. Over a productive working lunch, it was made plain that America did not want Australia to put up any roadblocks before Britain’s entry into the European Common Market (the forerunner to the EU).

When the Cuban Missile Crisis broke out in October, Menzies earned the administration’s admiration for being ‘among the first – if not the first’ head of government to support Kennedy’s firm stance. Menzies further earned Kennedy’s respect through his prestigious Jefferson Oration, delivered at the founding father’s Virginia home on US Independence Day 1963, a verbatim copy of which survives in Kennedy’s papers. After delivering the speech, Menzies travelled to nearby DC for his third lunch with the President, who gave a toast:

‘I know that all my fellow countrymen join me in expressing a warm welcome to the Prime Minister. I don’t think that there is any visitor that has more friends in the United States than the Prime Minister of Australia, and he has had those friends and kept them over a long period of time stretching back to the days of 1939. He has been a constant figure not only in his own country’s government, but also in the relations which exist between the United States and Australia. Those relations which permit the easiest kind of communication between the governments, which permit us to reach agreement on matters which in other countries might take much longer and might not be as nearly so satisfactorily resolved, have been a great source of encouragement to President Roosevelt, President Truman, President Eisenhower, and now to me.

So, Prime Minister, we want to express our gratification that you came and visited us on your way back home. The Prime Minister was raising the clans of Scotland while I was doing the same in Ireland a few days ago with equal effectiveness. But we appreciate his coming here. We are glad, particularly, that he came to us after visiting the home of one of our most distinguished Presidents, President Jefferson. I think the relationship between Australia and the United States is based not so much on sentiment and not only on self-interest – although there are, of course, those factors – but I think our confidence in Australia was built during two world wars, most particularly in the days of World War II and in the days that have followed when the United States and Australia have moved in such concert together.

I hope that our reputation in Australia has been maintained since World War II as a determined friend and also in Mr. Jefferson’s words as a “bold enemy.” I think that the days ahead for us both are going to be particularly critical. I am glad to have a chance to remind the American people, as well as the Government, that we should look not only east towards Europe but also west, towards the not always Pacific Ocean, and particularly look west towards our friends in Australia.

We are glad to have you here, Prime Minister – and members of your family – and I hope that you will all join with me in drinking to Her Majesty, the Queen.’

Despite this conviviality, Kennedy was less forthcoming when Menzies pressed him on the possibility of war with Indonesia stemming from its deliberate policy of Konfrontasi with Malaysia. By October, Kennedy went so far as to firmly rebuke External Affairs Minister Garfield Barwick, telling him ‘People have forgotten ANZUS and are not at the moment prepared for a situation which would involve the United States.’

Even if the relationship had soured based on political and strategic realities, when in the next month Kennedy was assassinated, Menzies was deeply moved as was much of the Western world. He felt compelled to address the Australian people with a televised speech in which he said:

‘Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve had terrible news today. The assassination of President Kennedy. This is of course a tremendous tragedy for the United States of America. It’s a tremendous tragedy in my opinion for the world. And of course, what it can mean in terms of horror and tragedy for Mrs. Kennedy, we may only imagine.

President Kennedy was a very remarkable man, young, vigorous, extremely able, full of courage, full of character. I saw a good deal of him in a limited period of time over the last three years. And I came to admire him tremendously.

And I’m sure you did, because he did give to the western world another source of strength in powerful leadership determination. You look back not so very long ago to the time he confronted the Soviet Union over Cuba and produced from them an agreement to withdraw Soviet arms and troops from Cuba.

This was of tremendous importance for the free world. I believe it was one of the turning points in recent history. What will happen now? I don’t know. All I know is that it will take some time for the new president to settle in, so to speak. And it will be some time before we forget how tremendously indebted the free world has been to John Kennedy and the work that he did.

I do hope that the dangers of the world will not be too much increased by this horrible event. That they will be somewhat increased, I’m afraid I have no doubt. We would like all of us, wouldn’t we, to send our sympathy to Mrs. Kennedy and her family, and to the American people as a whole.’

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.